Screen

-

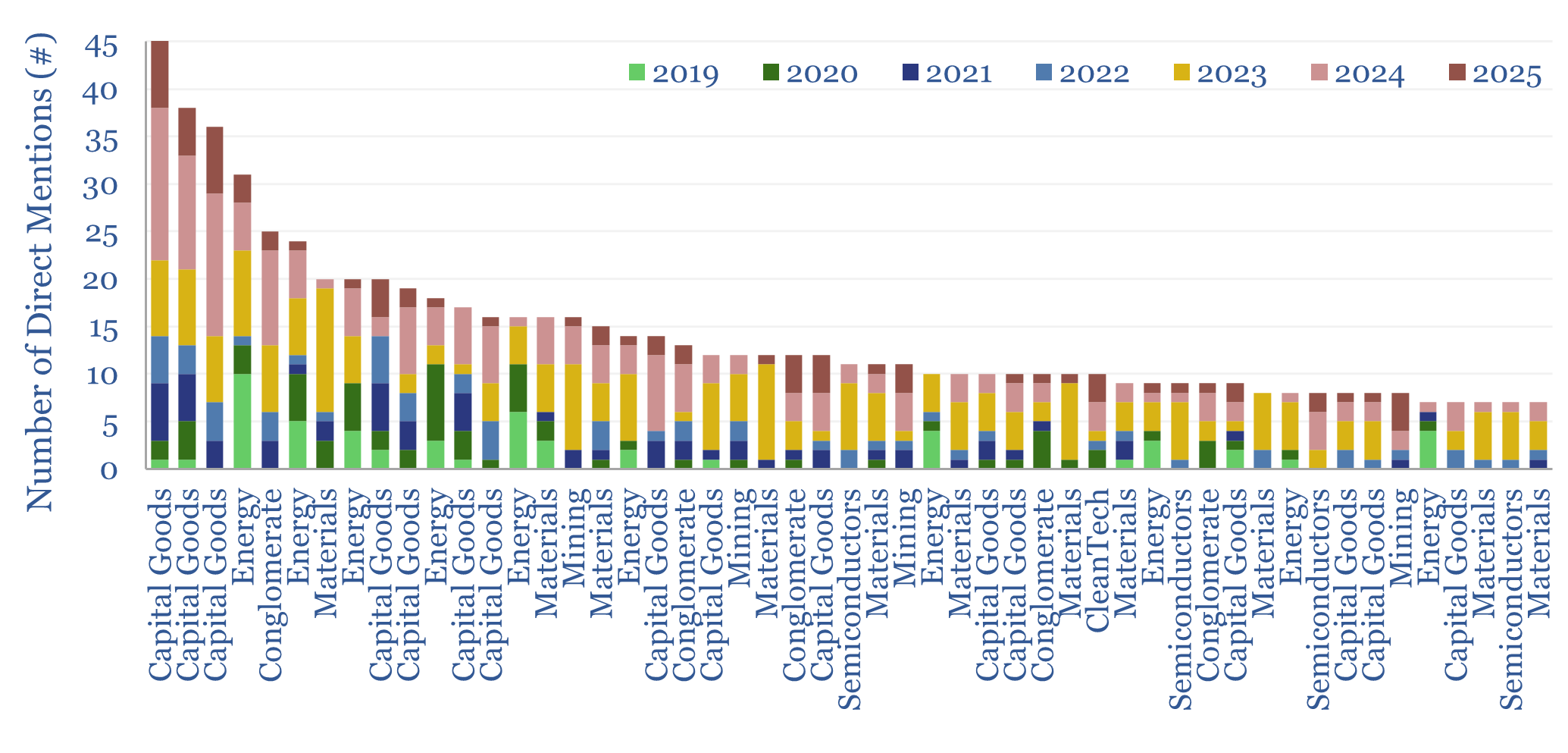

Energy technology and energy transition companies?

This database contains a record of every company that has ever been mentioned across Thunder Said Energy’s energy technology research, as a useful reference for TSE’s clients. The database summarizes 3,000 mentions of 1,700 energy transition companies, broader energy producing and consuming companies, their size, focus and a summary of our key conclusions, plus links…

-

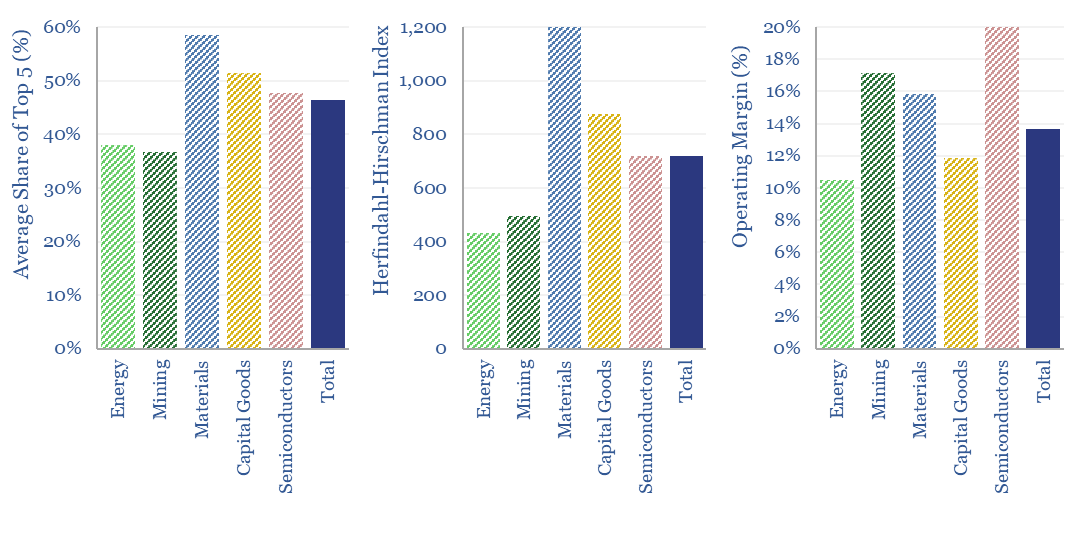

Market concentration by industry in the energy transition?

What is the market concentration by industry in energy, mining, materials, semiconductors, capital goods and other sectors that matter in the energy transition? The top five firms tend to control 45% of their respective markets, yielding a ‘Herfindahl Hirschman Index’ (HHI) of 700.

-

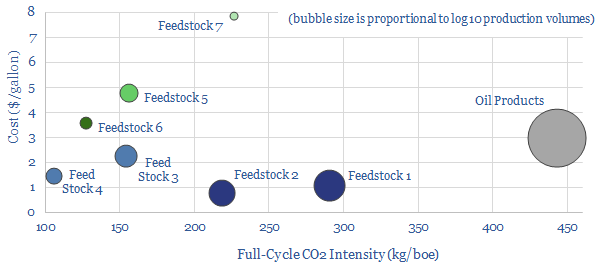

Biofuel technologies: an overview?

Biofuels are currently displacing 3.5Mboed of oil and gas. But they are not carbon-free, and their weighted average CO2 emissions are only c50% lower. This data-file breaks down the biofuels market across seven key feedstocks, to help identify which opportunities can scale for the lowest costs and CO2, versus others that require further technical progress.

-

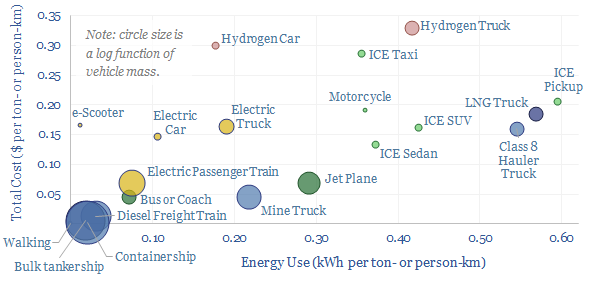

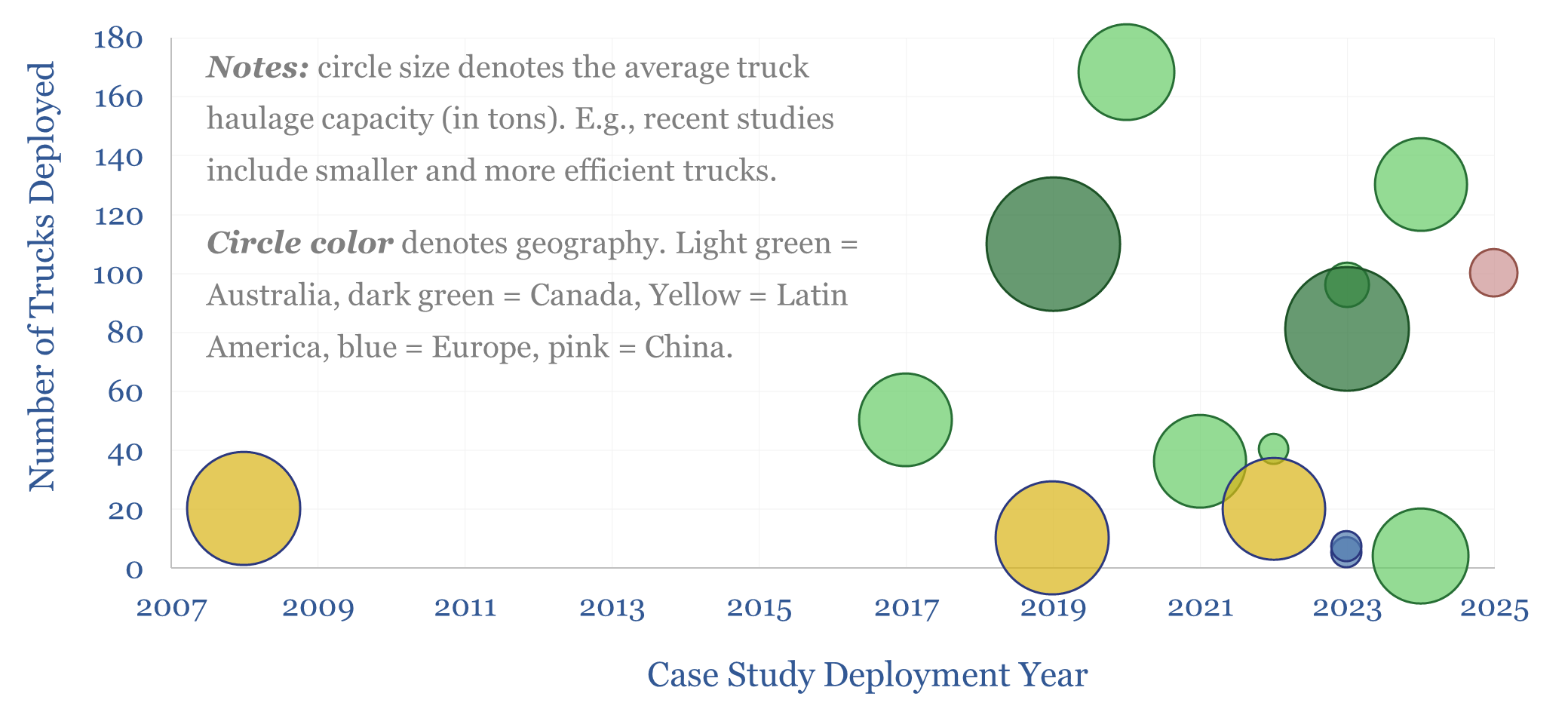

Vehicles: energy transition conclusions?

Vehicles transport people and freight around the world, explaining 70% of global oil demand, 30% of global energy use, 20% of global CO2e emissions. This overview summarizes all of our research into vehicles, and key conclusions for the energy transition.

-

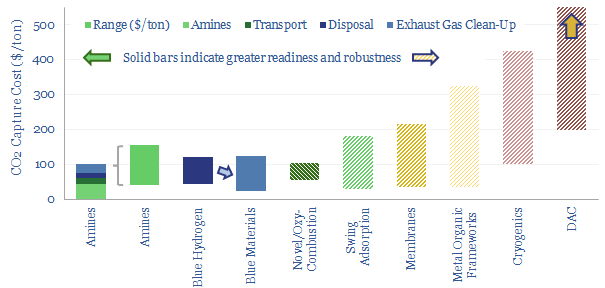

Carbon capture and storage: research conclusions?

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) prevents CO2 from entering the atmosphere. Options include the amine process, blue hydrogen, novel combustion technologies and cutting edge sorbents and membranes. Total CCS costs range from $80-130/ton, while blue value chains seem to be accelerating rapidly in the US. This article summarizes the top conclusions from our carbon capture…

-

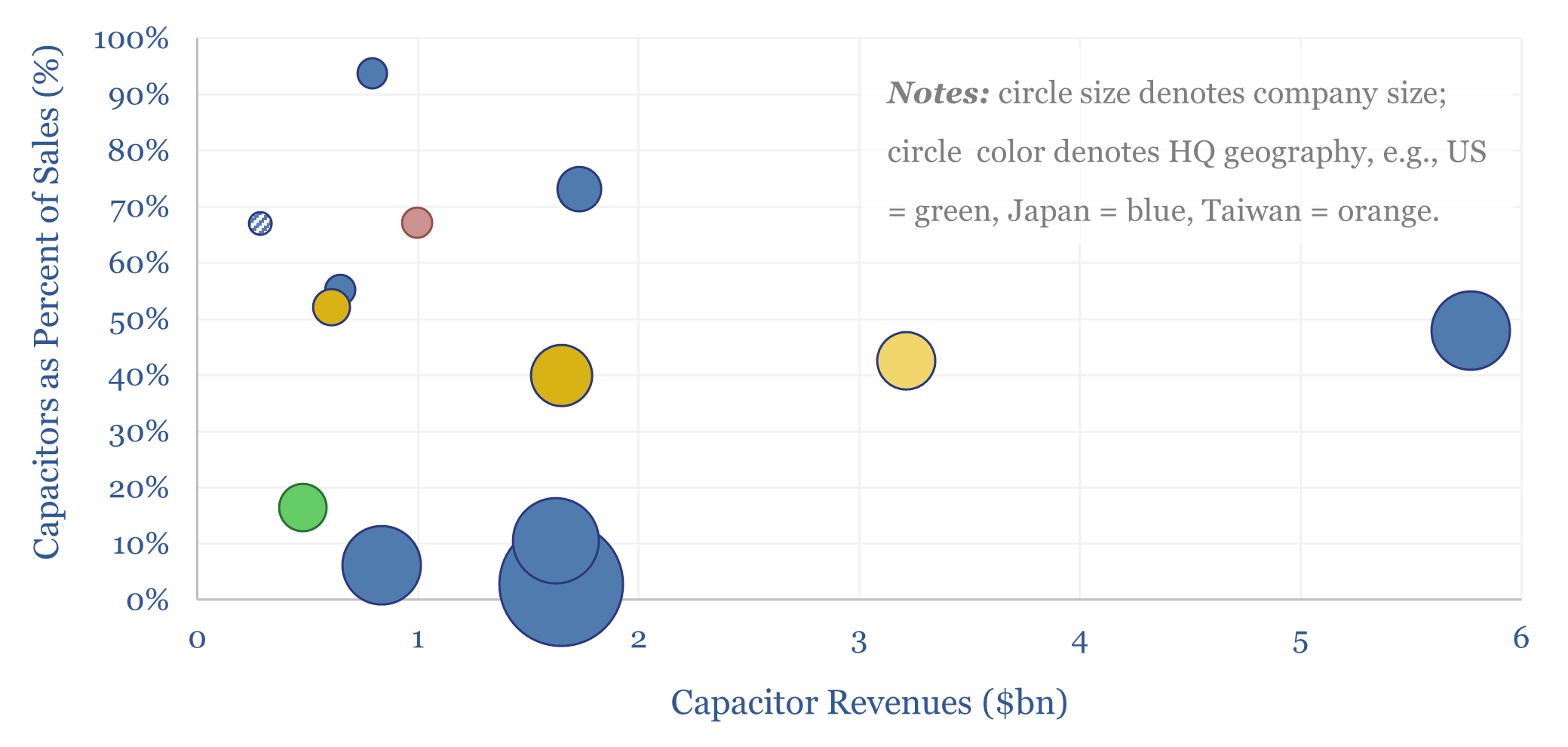

Capacitor market: leading companies?

This data-file profiles a dozen leading companies in capacitors, which control two-thirds of the $30bn pa global market. Many companies also produce other passive electronic components, sensors and MOSFETs. Hence will the rise of AI, especially transient-heavy data-centers, pull on demand?

-

Smart meter installations by region over time?

Our smart meter data-file cpatures 1.1bn global smart meter installations by region and over time. Smart meters automate the submission of consumption data to the grid, while opening the door to real-time monitoring and load disaggregation, which can reduce total demand by 9% and peak demand by 13%. Opportunities are growing alongside AI. Leading companies…

Content by Category

- Batteries (89)

- Biofuels (44)

- Carbon Intensity (49)

- CCS (63)

- CO2 Removals (9)

- Coal (38)

- Company Diligence (95)

- Data Models (840)

- Decarbonization (160)

- Demand (110)

- Digital (60)

- Downstream (44)

- Economic Model (205)

- Energy Efficiency (75)

- Hydrogen (63)

- Industry Data (279)

- LNG (48)

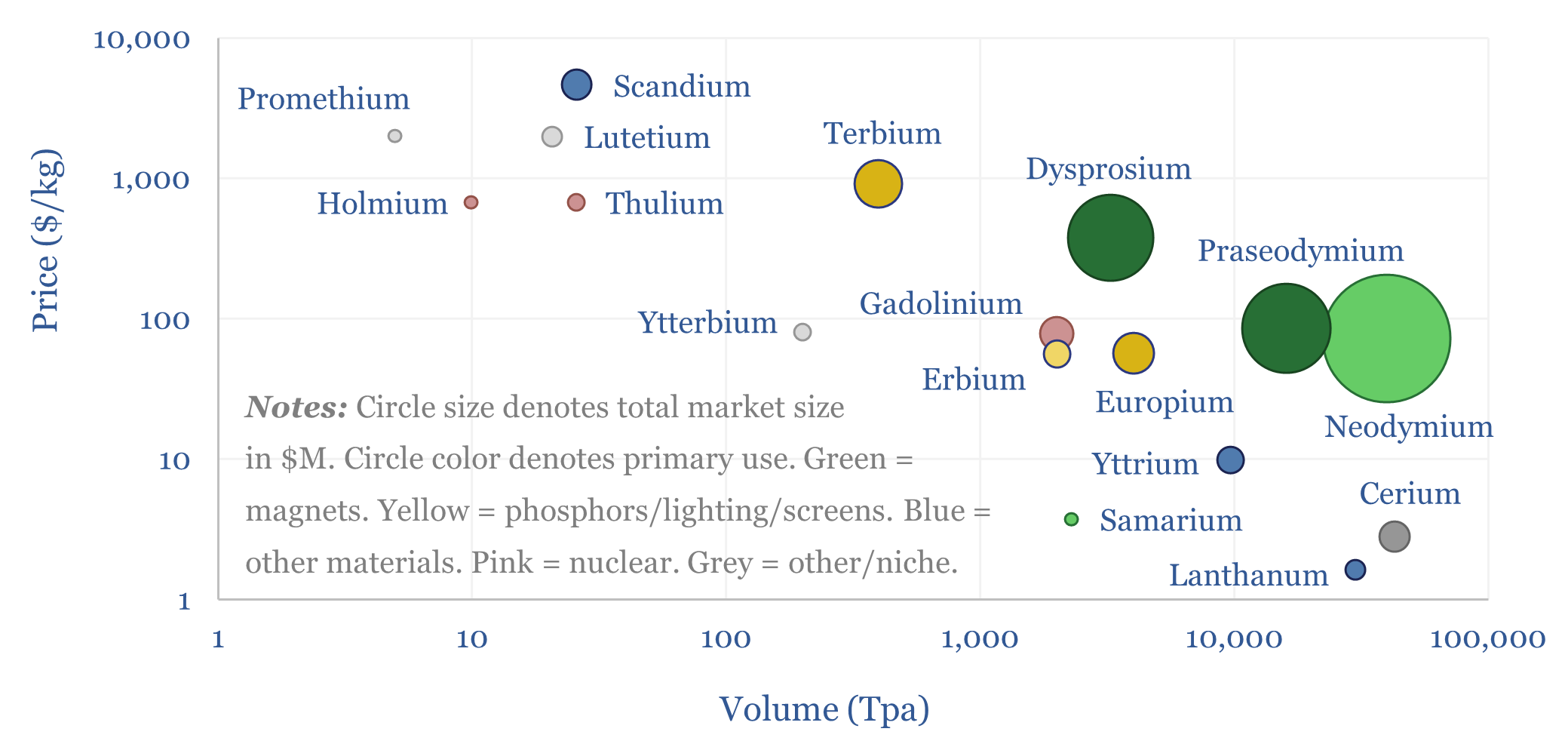

- Materials (82)

- Metals (80)

- Midstream (43)

- Natural Gas (149)

- Nature (76)

- Nuclear (23)

- Oil (164)

- Patents (38)

- Plastics (44)

- Power Grids (130)

- Renewables (149)

- Screen (117)

- Semiconductors (32)

- Shale (51)

- Solar (68)

- Supply-Demand (45)

- Vehicles (90)

- Wind (44)

- Written Research (354)