Investors may suffer if they do not consider the energy transition. But they may suffer more if they consider it, and get the answer wrong. We argue that the best way to drive the energy transition will be to maximise carbon-adjusted investment returns.

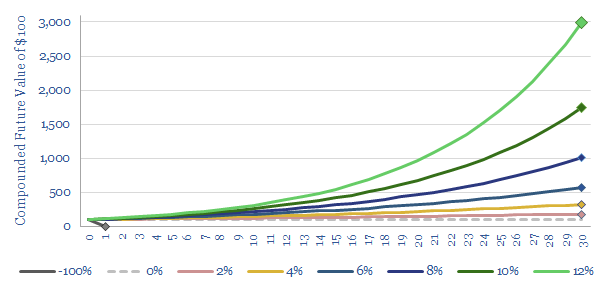

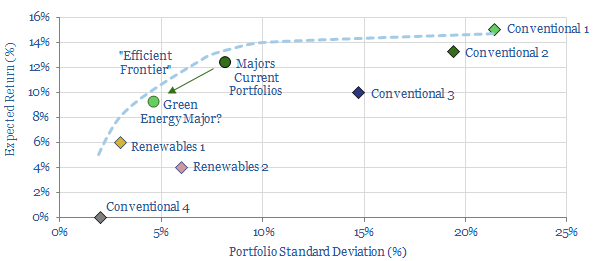

Our starting point is the chart below, which focuses on the power of compound interest, “the most powerful force in the universe” (the quote has been ascribed to Albert Einstein). This is not our usual tack — which focuses upon energy technologies, economics or quantifying CO2 — but purely mathematics…

The difference is enormous between compounding at, say, 4% and 12%. It may not sound material in any given year (“it’s just 8%”). But over a thirty year investment horizon, it makes the difference between a $100 initial investment rising to c$300 and $3,000 of value (i.e., a factor of 10x).

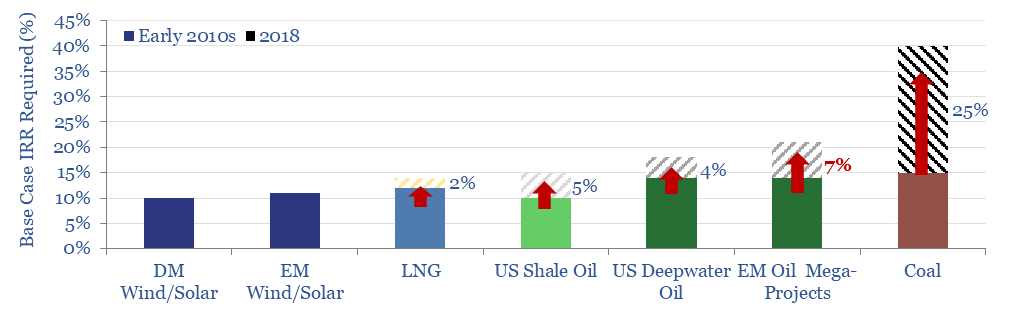

How this applies to the energy transition is that we currently observe institutional investors backing away from high-return (10-20% per year), industrial asset classes, which are feared to be high-carbon, towards low-returning asset classes (4-6% per year), which are perceived to be low-carbon.

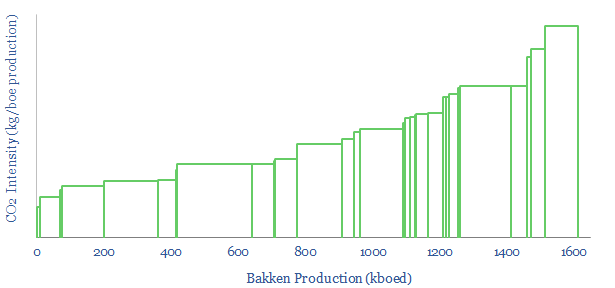

For oil companies, the spread of opportunites is charted below (note here). Measured over any single year the difference may be imperceptible. But over 30-years it is vast.

By down-shifting from high-return assets to low-return assets, the costs of mitigating climate change end up falling upon the shoulders of institutional investors: endowments, foundations, hopeful retirees; as a hidden cost.

It is not for us to say whether this kind of hidden cost is morally right or wrong. But we can say that it is sub-optimal, in economic terms, because unlike a visible cost (e.g., a direct “carbon price”), it will not change behaviours in ways that actually drive decarbonisation.

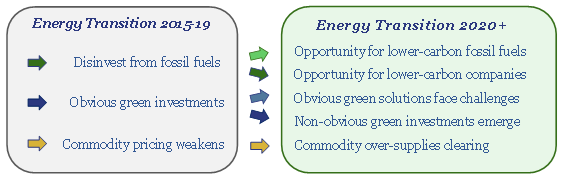

No “incremental” energy transition occurs when investors divest from traditonal industrial sectors; and instead, outbid each other to finance the same renewable energy projects. A better alternative is needed.

Investment firms understand the challenge. This week, Blackrock’s CEO, Larry Fink, published a letter to CEOs, stating how climate change will “fundamentally re-shape finance”. What is not being reshaped, of course, is the maths of compound returns. Mr Fink’s letter begins by highlighting “we have a deep responsibility to institutions and individuals … to promote long-term value”. So how can this happen?

Three better alternatives for investors in the energy transition

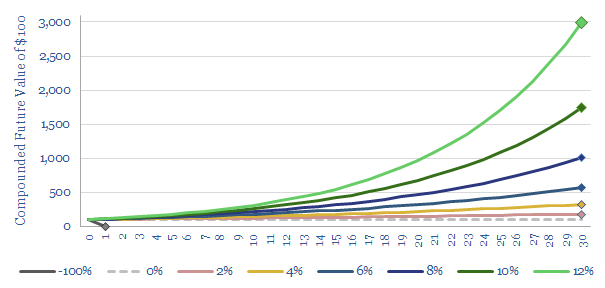

In order to drive incremental energy transition, it is necessary to attract incremental capital. It must flow towards high-returning technologies and projects, which can drive decarbonization. This is our central tenet on investing for an energy transition. And it underpins the opportunities that excite us most in 2020 (chart below), which should all seek double-digit returns. Seen this way, climate change is not a cost to be passed on to investors, but a positive investment opportunity, to help meet a societal need.

A second alternative is to allocate more capital to companies that offer attractive returns and also have lower carbon contributions than their peers: such as lower-CO2 oil and gas producers, shale producers, refiners, midstream or chemicals companies. On any decarbonized energy model that we can construct, demand for gas will rise and demand for low carbon oil will not collapse. We have reams of data to help you with this screening. Often it is due to superior technologies.

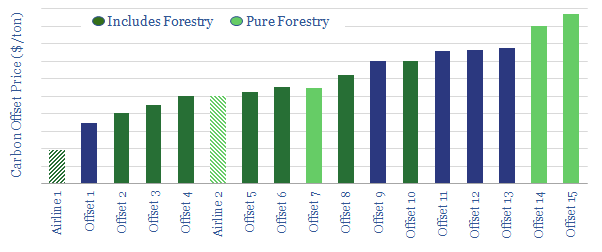

A third alternative could be to offset CO2 directly, as you continue investing in high-returning, industrial companies. This still leaves investors paying for the cost of climate change out of their future returns. But the cost is much lower than if investment returns are sacrificed by divesting from industrial companies and funding renewables.

For example, we recently tabulated the costs of carbon credits, being offered by 15 separate offset schemes. Based on the data, we calculate that an investor could buy a SuperMajor oil company with an average distribution yield of 7%; offset their investment’s entire Scope 1&2 emissions for a drag of just 0.5pp; leaving their “zero carbon cash yield” at 6.5%. (It will be interesting which forward-thinking Super-Major is first to apply this logic and offer up such a “carbon-offset share class”).

The end point is that high carbon companies will see higher capital costs (and our survey work indicates this is already occurring, chart below). But how much higher? In an efficient carbon market, there is an easy answer: high enough so that the extra yield of Investment X (vs Investment Y) can be re-invested in carbon credits to offset the extra CO2 of Investment X (vs Investment Y).

These ‘carbon adjusted returns’ are directly comparable. The higher carbon- and risk- adjusted return equates to the better investment. The higher the carbon price, the higher the relative cost of capital for high-carbon companies; and the higher the relative incentive to lower emissions.

This system, we believe, will be much more sophisticated and effective in driving a full-scale energy transition that the blunt-force strategy of “divest from oil and buy renewables”. It will also not leave investors short-changed, by up to 90%, when they come to meet their budgeting or retirement needs in 2050.

Please do contact us if you have any observations, questions or comments; or would like to discuss some of the “long-term value” opportunities, which we think can help drive the energy transition…