-

China: can the factory of the world decarbonize?

China now aspires to reach ‘net zero’ CO2 by 2060. But is this compatible with growing an industrial economy and attaining Western living standards? The best middle-ground sees China’s coal phased out and gas rising by a vast 10x to 300bcfd. The biggest challenges are geopolitics and sourcing enough LNG.

-

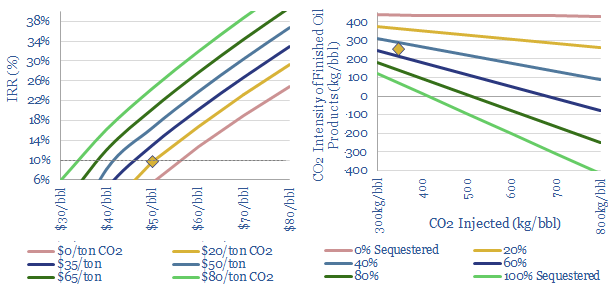

CO2-EOR: well disposed?

CO2-EOR is the most attractive option for large-scale CO2 disposal. Unlike CCS, which costs over $70/ton, additional oil revenues cover the costs of sequestration. And the resultant oil is 50-100% lower carbon than usual. The technology is mature. Potential exceeds 2GTpa. This 23-page report outlines the opportunity.

-

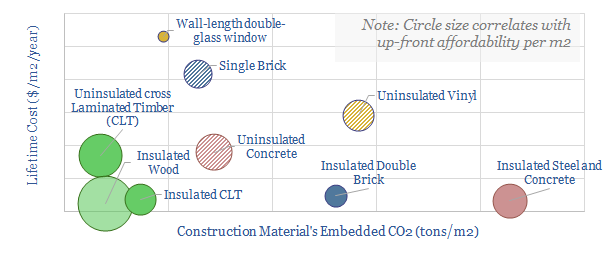

Carbon negative construction: the case for mass timber?

Construction accounts for 10% of global CO2, mainly due to cement and steel. But mass timber could become a dominant new material for the 21st century, lowering emissions 15-80% at no incremental cost. Debatably mass timber is carbon negative if combined with sustainable forestry. We outline the opportunity.

-

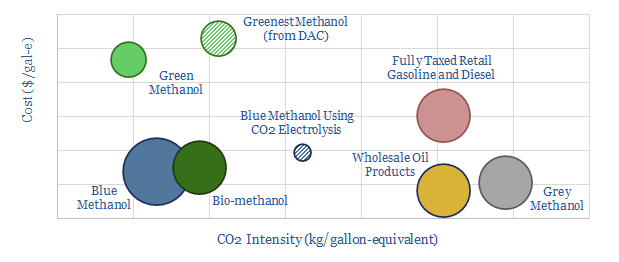

Methanol: the next hydrogen?

Methanol is becoming more exciting than hydrogen as a clean fuel to help decarbonize transport. Specifically, blue methanol and bio-methanol are 65-75% less CO2-intensive than oil products, while they already earn 10% IRRs at c$3/gallon prices. Unlike hydrogen, it is simple to transport and integrate methanol with pre-existing vehicles.

-

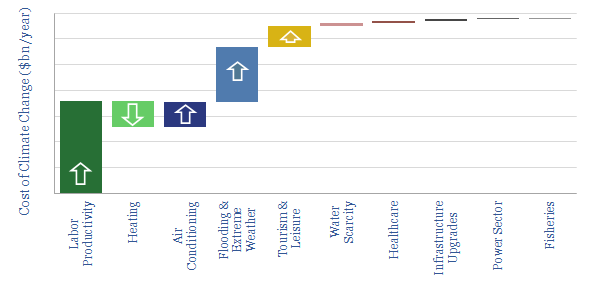

Costs of climate change: a paradox?

The unmitigated costs of climate change will likely reach $1.5trn per annum after 2050, exerting an enormous toll on the world. However, the costs of the energy transition will exceed $3trn per annum. Our 14-page note explores whether this mismatch matters. Could it even undermine the energy transition?

-

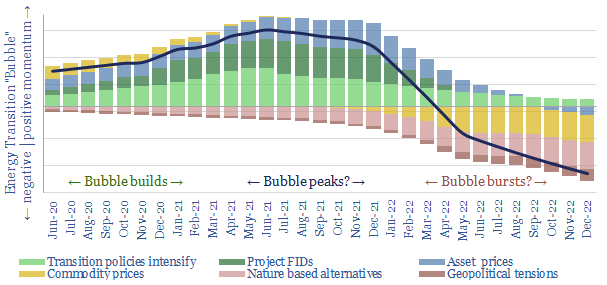

Ten Themes for Energy in 2021?

This note outlines our top ten themes for 2021. We fear Energy Transition will continue building into an investment bubble. But also appearing on the horizon this year are three triggers to burst the bubble. We continue to prefer non-obvious opportunities in the transition.

-

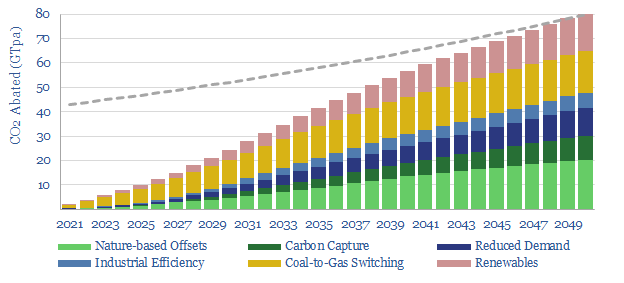

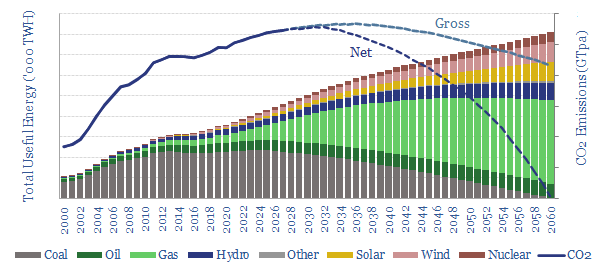

Decarbonizing global energy: the route to net zero?

The global energy system can be fully decarbonized by 2050, for an average CO2 cost of $42/ton. Remarkably, this is almost half the cost foreseen one year ago. 85Mbpd of oil and 375TCF pa of gas are still required in this 2050 energy system, together with efficiency technologies, carbon capture and offsets.

-

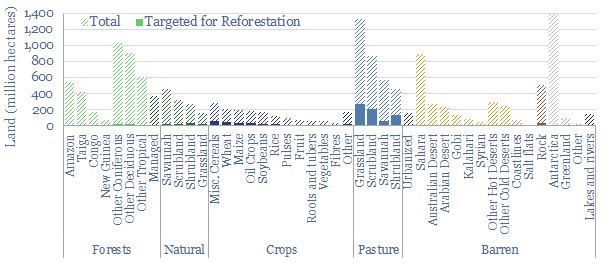

How much land is available for reforestation?

2.3bn hectares of land have been deforested, releasing c25% of all anthropogenic emissions. This 19-page note concludes 1.2bn hectares can be reforested. Consequently, there is room for 85Mbpd of oil and 400TCF of gas in a decarbonized energy system, while half of all ‘new energies’ may not be needed.

-

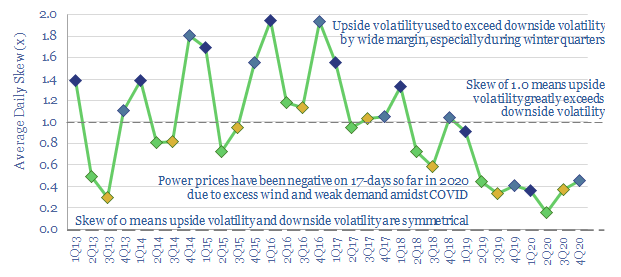

Prevailing wind: new opportunities in grid volatility?

UK wind power has almost trebled since 2016. But its output is volatile, now varying between 0-50% of the total grid. Hence this 14-page note assesses the volatility, using granular, hour-by-hour data from 2020, to outline which backup opportunities are best-placed.

-

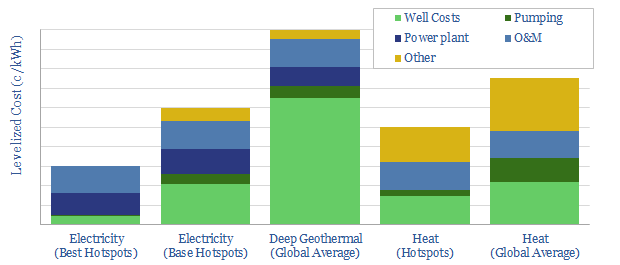

Geothermal energy: what future in the transition?

Drilling wells and lifting fluids to the surface are core skills in oil and gas. Hence could geothermal be a natural fit in the energy transition? Next-generation geothermal economics can be very competitive, both for power and heat. Pilot projects are accelerating. This 17-page note presents the opportunity.

Content by Category

- Batteries (89)

- Biofuels (44)

- Carbon Intensity (49)

- CCS (63)

- CO2 Removals (9)

- Coal (38)

- Company Diligence (94)

- Data Models (838)

- Decarbonization (160)

- Demand (110)

- Digital (59)

- Downstream (44)

- Economic Model (204)

- Energy Efficiency (75)

- Hydrogen (63)

- Industry Data (279)

- LNG (48)

- Materials (82)

- Metals (80)

- Midstream (43)

- Natural Gas (148)

- Nature (76)

- Nuclear (23)

- Oil (164)

- Patents (38)

- Plastics (44)

- Power Grids (130)

- Renewables (149)

- Screen (117)

- Semiconductors (32)

- Shale (51)

- Solar (68)

- Supply-Demand (45)

- Vehicles (90)

- Wind (44)

- Written Research (354)