We have reviewed 14 mass extinctions over the past 500M years, in order to draw five conclusions on systemic risk amidst the energy transition. Current policies may be short-sighted. Improved technologies and nature-based solutions could likely fare better.

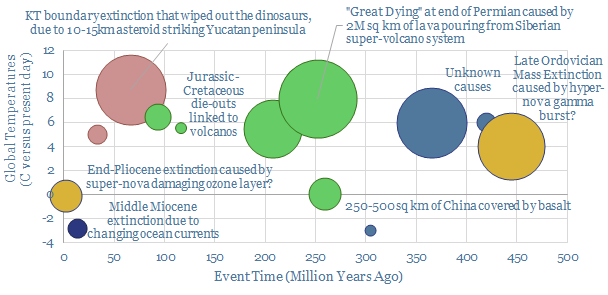

Mass extinctions are the ultimate “systemic risks” as they tend to wipe out an average of 50% of all life on Earth (for perspective, Coronavirus has wiped out about 0.05-0.1% of humanity). In almost all cases in our data-file, they are caused by exogenous shocks, which also change the global climate, either by warming it or cooling it. Eventually life has rebounded, although it can take 30M years, while re-balancing the planet towards a different mix of species than came before. Full details can be downloaded here.

If you were to draw a spectrum of cataclysmically bad things that can happen to the world, mass extinctions would probably lie at the extreme. Hence five conclusions and insights follow below from our data-set…

(1) Mass extinctions happen every 15-30M years. This includes 14 events over the past 500M years, through to 4 events over the past 65M years. The numbers are likely towards the more frequent end of the range, as the rock record turns over every 100-300M years, making it hard to detect smaller extinction events from the distant past. This implies that for every 15M year period, there is approximately a “one-in-a-million” chance of a mass extinction event threatening the majority of all life on Earth. Small but not zero.

(2) Are risks preventable? A good, common-sense principle of risk-management is that you should care just as much about low-probability high-impact risks as you care about high-probability low-impact risks. This is why people buy life insurance. But it is hard to see how you protect against vast outpourings from super-volcanos (5 events), enormous asteroids (2 events) or supernovas stripping the world of its ozone layer (2 events). My intuition here is that there is no way to “eliminate” systemic risks that might make the world unlivable.

(3) Policies are effectively useless at preventing many systemic risks. Try banning a volcano from erupting, a virus from mutating or a war from breaking out. There are two thoughts here that keep me up at night: (a) policies focused at averting climate change are at the top of every policymaker’s list right now, but is this coming at the cost of ignoring and thereby inflating other significant systemic risks? (b) worse, will policies focused at averting climate change actually exacerbate some systemic risks? Some examples from our research are here, here and here.

(4) Improved technologies may be a better focus area, as they lower systemic risks across the board. I say this after receiving my second dose of the Moderna vaccine this week. And recalling that totally realistic scene in Armageddon where Bruce Willis flies a rocket to an asteroid and blows it up using nuclear weapons. The thought that fascinates me is how inextricably human resiliency to systemic risks is bound up with energy technologies. This is a rationale for our renewed focus on energy technologies (below).

(5) Nature based solutions? We are currently undergoing one of the greatest mass extinction events in the history of the planet, destroying over one-third of the world’s forests since pre-industrial times, over half of some blue carbon eco-systems and threatening up to 1M species. Solving this problem is the direct rationale for nature-based solutions to climate change, which do not simply use trees to remove CO2 from the atmosphere, but also tackle the underlying issue of not destroying the planet. We argue nature-based activities will emerge as the single largest focus in the energy transition (note below).