This 17-page note makes the largest changes to our shale forecasts in five years, amidst evidence that productivity growth is slowing. Productivity now peaks after 2025, precisely as energy markets hit steep undersupply. Our shale outlook still sees +1Mbpd/year of liquids potential through 2030, but it is back loaded, and requires persistently higher oil prices?

We spent summer of 2017, reading several hundred technical papers from the US shale industry, and published a 200-page book arguing shale was a “new technology paradigm, a digital revolution, offering 50-70% further productivity gains” as ever-improving productivity unlocked the potential to add 2Mbpd of supply each year, and ultimately ramp past 25Mbpd by 2030 in a completely unconstrained scenario. This was 2017. Most people believed shale was ‘dead’ at $60/bbl. Indeed, forecasters such as the EIA/IEA were projecting 5-7Mbpd of shale oil in 2025-30.

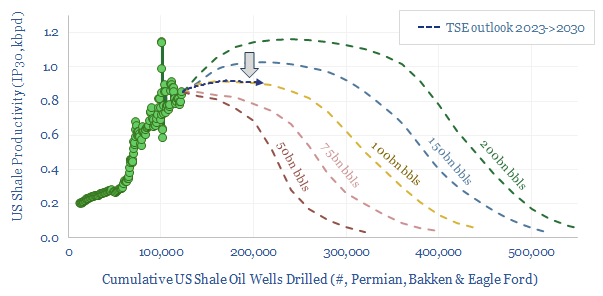

This 17-page note contains the largest revisions to our shale outlook since 2017. It is hard to ‘fit a depletion curve’ onto US shale productivity. But in 2017, we would have picked the dark green line (chart above), with 200bn bbls of liquid resources remaining, which simplistically, at a 20-year RP ratio, would land in the 25-30Mbpd production range. Our latest forecasts are shown by the dark blue line and maybe 100bn bbls remain.

Quantitative evidence for slowing productivity is discussed on pages 4-7. Productivity data has moved sideways for 3-years now in the Permian, but there are also important trends and data interpretation issues.

Qualitative evidence for slowing productivity is discussed on pages 8-10. We reviewed the technical papers from URTEC in 2023 (one E&P really stood out). Productivity improves more slowly from here?

Changes to our forecasts for productivity, shale production growth, ultimate production potential, year-by-year supply, activity, oil prices and shale E&P free cash flow are all discussed on pages 10-16.

How wrong were we? In 2017, we heavily caveated our shale forecasts, noting that “world-changing trends are rarely realized in smooth trajectories” and the most likely reason we would be wrong would be because shale’s smooth production growth would be disrupted by “periodic oil price volatility”. At the time we envisaged the volatility to stem from OPEC policies. Ironically, it was COVID, war, rate rises and the ESG movement, while OPEC itself has recently been acting as a stabilizing force! The de-railing impacts of volatility may be important to consider for other energy transition technologies that are widely hoped to ramp up in a perfect, uninterrupted straight line (pages 17-18).