LNG

-

LNG: top conclusions in the energy transition?

Thunder Said Energy is a research firm focused on economic opportunities that drive the energy transition. Our top ten conclusions into LNG are summarized below, looking across all of our research.

-

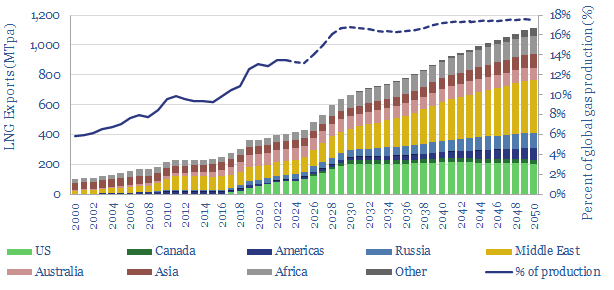

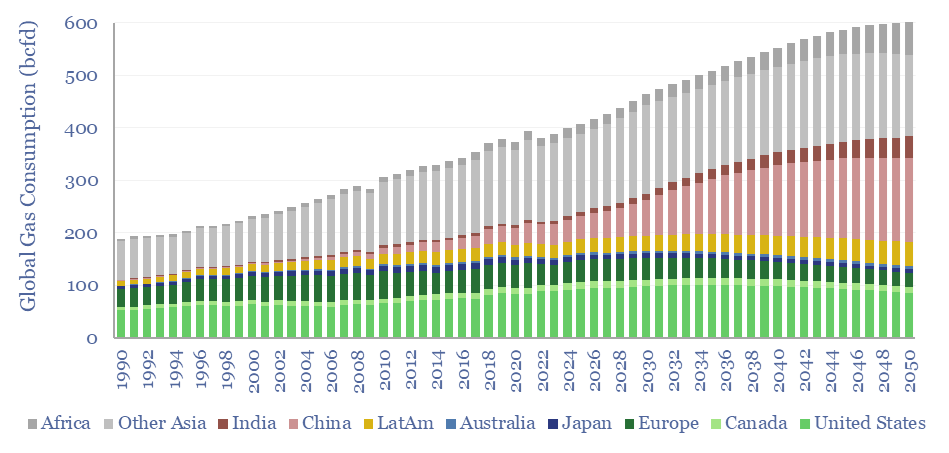

Global gas supply-demand in energy transition?

Global gas supply-demand is predicted to rise from 400bcfd in 2023 to 600bcfd by 2050, in our outlook, while achieving net zero would require ramping gas even further to 800bcfd, as a complement to wind, solar, nuclear and other low-carbon energy. This data-file quantifies global gas demand and supply by country.

-

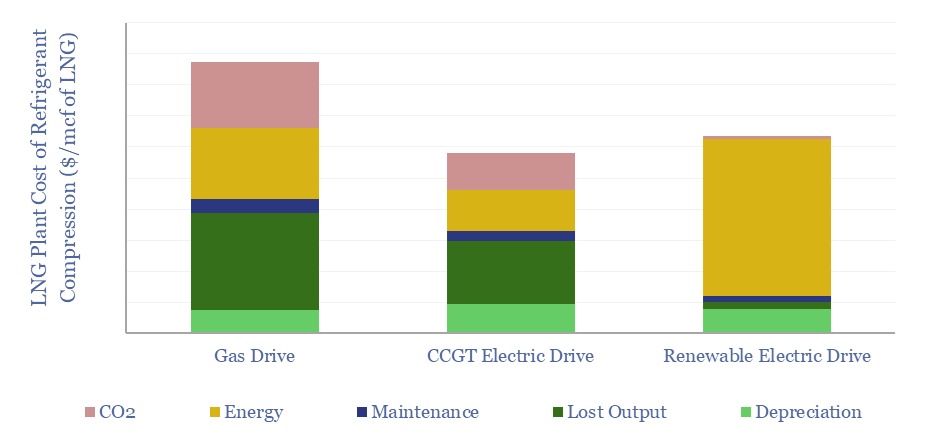

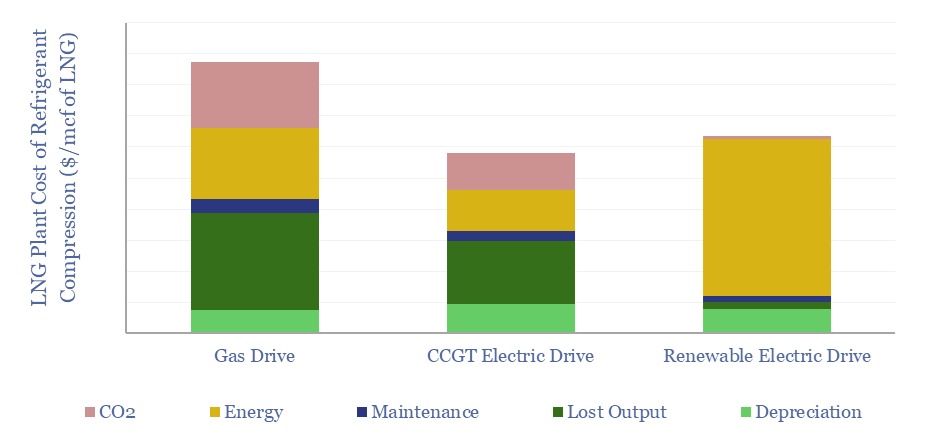

LNG plant compressors: chilling goes electric?

Electric motors were selected, in lieu of industry-standard gas turbines, to power the main refrigeration compressors at three of the four new LNG projects that took FID in 2024. Hence is a major change underway in the LNG industry? This 13-page report covers the costs of e-LNG, advantages and challanges, and who benfits from shifting…

-

LNG plant compression: gas drives vs electric motors?

This data-file compares the costs of refrigerant compression at LNG plants, using gas turbines, electric motors powered by on-site CCGTs, or electric motors powered by renewable electricity. eLNG has higher capex costs, but higher efficiency, lower opex, and short payback times. Numbers in $/mcf and $/MTpa can be stress-tested in the data-file.

-

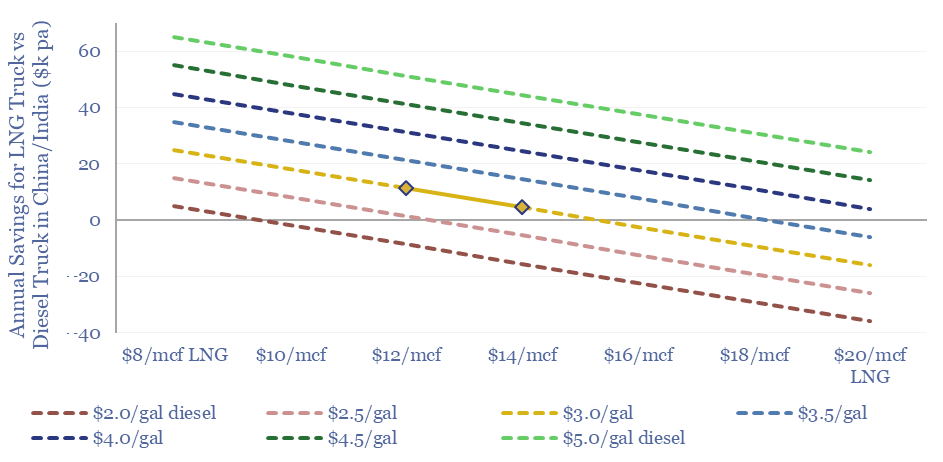

LNG trucks: Asian equation?

LNG trucking is more expensive than diesel trucking in the developed world. But Asian trucking markets are different, especially China, where exponentially accelerating LNG trucks will displace 150kbpd of oil demand in 2024. This 8-page note explores the costs of LNG trucking and sees 45MTpa of LNG displacing 1Mbpd of diesel?

-

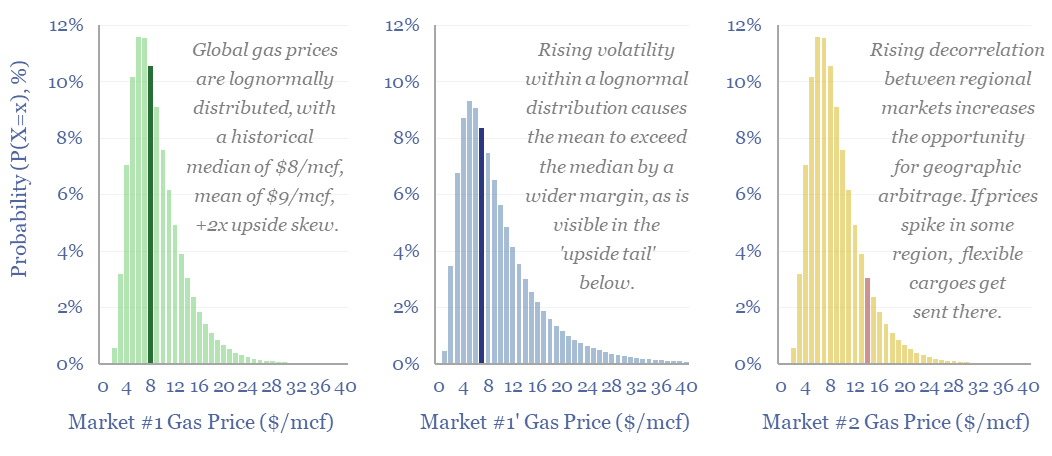

Energy trading: value in volatility?

Could renewables increase hydrocarbon realizations? Or possibly even double the value in flexible LNG portfolios? Our reasoning in this 14-page report includes rising regional arbitrages, and growing volatility amidst lognormal price distributions (i.e., prices deviate more to the upside than the downside). What implications and who benefits?

-

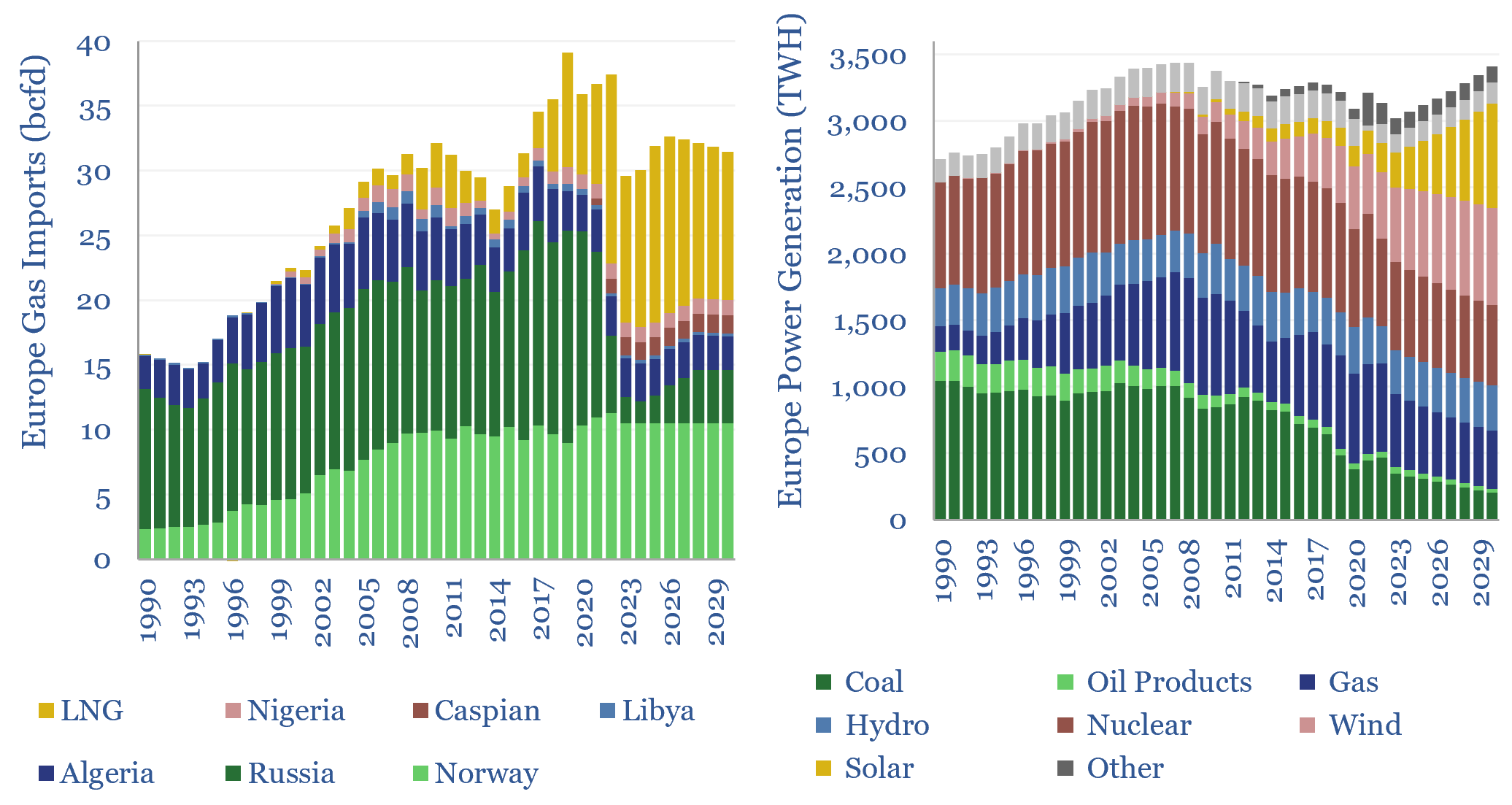

European gas and power model: natural gas supply-demand?

European gas and power markets will look better-supplied than they truly are in 2023-24. A dozen key input variables can be stress-tested in the data-file. Overall, we think Europe will need to source over 15bcfd of LNG through 2030, especially US LNG.

-

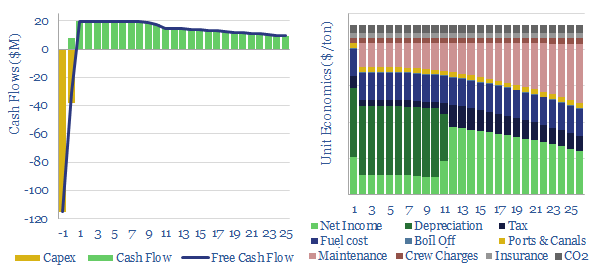

Liquefied CO2 carriers: CO2 shipping costs?

This model captures the economics of a CO2 carrier, i.e., a large marine vessel, carrying liquefied CO2, at -50ºC temperature and 6-10 bar pressure, for CCS. A good rule of thumb is seaborne CO2 shipping costs are $8/ton/1,000-miles. Shipping rates of $100k/day yield a 10% IRR on a c$150M tanker.

-

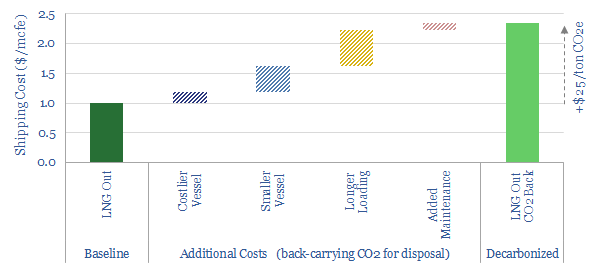

Decarbonized gas: ship LNG out, take CO2 back?

This note explores an option to decarbonize global LNG: (i) capture the CO2 from combusting natural gas (ii) liquefy it, including heat exchange with the LNG regas stream, then (iii) then send the liquid CO2 back for disposal in the return journey of the LNG tanker. There are some logistical headaches, but no technical show-stoppers.…

-

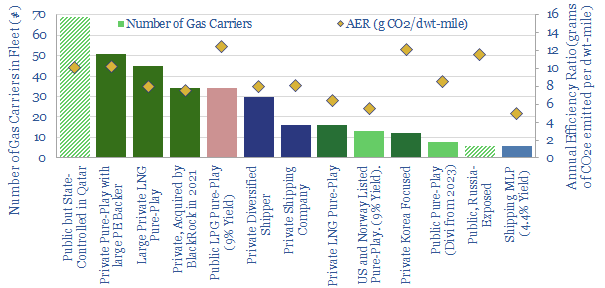

LNG shipping: company screen?

This data-file is a screen of LNG shipping companies, quantifying who has the largest fleet of LNG carriers and the cleanest fleet of LNG carriers (i.e., low CO2 intensity). Many private companies are increasingly backed by private equity. Many public companies have dividend yields of 4-9%.

Content by Category

- Batteries (89)

- Biofuels (44)

- Carbon Intensity (49)

- CCS (63)

- CO2 Removals (9)

- Coal (38)

- Company Diligence (94)

- Data Models (838)

- Decarbonization (160)

- Demand (110)

- Digital (59)

- Downstream (44)

- Economic Model (204)

- Energy Efficiency (75)

- Hydrogen (63)

- Industry Data (279)

- LNG (48)

- Materials (82)

- Metals (80)

- Midstream (43)

- Natural Gas (148)

- Nature (76)

- Nuclear (23)

- Oil (164)

- Patents (38)

- Plastics (44)

- Power Grids (130)

- Renewables (149)

- Screen (117)

- Semiconductors (32)

- Shale (51)

- Solar (68)

- Supply-Demand (45)

- Vehicles (90)

- Wind (44)

- Written Research (354)