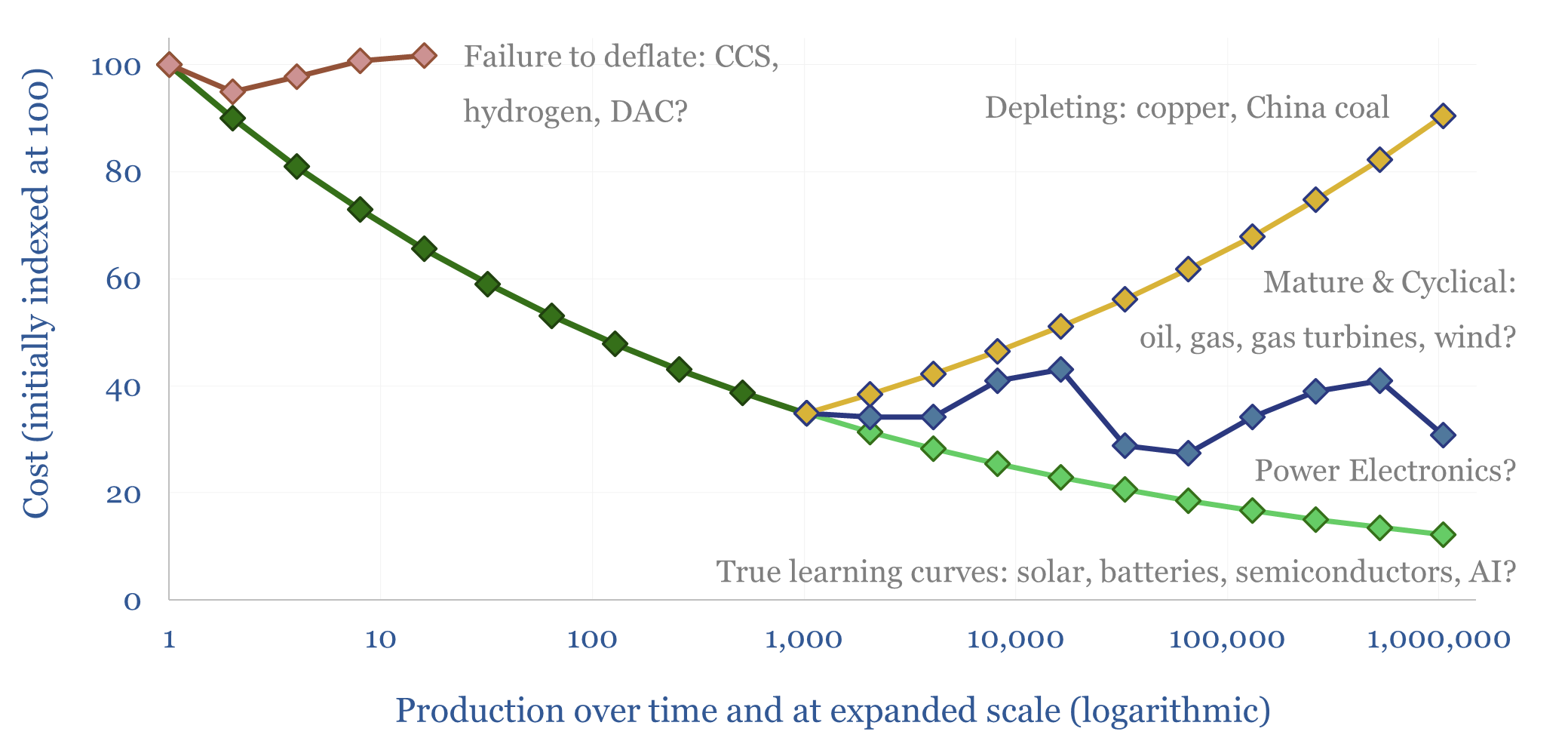

How much of the market’s current disenchantment with new energies can be attributed to persistently high costs, which failed to deflate as much as had been hoped? This 15-page report reviews the evidence. Cost trajectories have varied vastly. CCS and hydrogen cost more than initially advertised. Wind costs recently re-inflated. Yet, solar, electronics and lithium ion batteries remain exceptional?

“New energies costs will progressively deflate over time, due to economies of scale and learning curve effects” “New energies might cost more initially, but progressive deflation will ultimately mean decarbonizing the global economy costs less than continuing with the status quo”. “New energy might require subsidies at first, but ultimately these subsidies will pay for themselves many times over, by deflating the costs of new energies, to the bottom of the energy cost curve”.

The quotations above are meant to capture arguments that we have heard repeatedly over the past decade, especially from new energies advocates. In this 15-page report, we will take an unbiased and objective look at these claims.

Why now? Frankly, sentiment around new energies and decarbonization has never been so weak, at any point in the past decade. It feels like enthusiasm for “anything green” is at a low point. Perhaps this is overlooking important differences in the cost trajectories of different new energies categories. Some have deflated faster in the past, and will continue deflating impressively in the future?

Five myths about new energies cost deflation are challenged in the report, drawing on our favorite examples and charts. Generally prices tend to rise not fall (page 3), increased activity is inflationary not deflationary (pages 4-5), and project costs have come in above advertised levels for new energies such as CCS and green hydrogen electrolyers (pages 6-7).

Onshore wind costs have deflated in the past, but interestingly, the recent evidence shows quite steep re-inflation, possilby a transition to becoming a more mature and cyclical industry? (page 8). Or perhaps another contributor is that policymakers have subsidized wind, and other new energies. Subsidies are the enemy of deflation, based on the evidence we have reviewed (page 9).

Solar exceptionalism. The depressing discussion above makes solar stand out, and to a lesser extent, makes lithium ion batteries stand out (charts in the report). These categories have deflated most sharply in the recent past, and our forecasts are for continued deflation in the future (pages 11-13).

As a post-script, we also distinguish between the long-term price trajectories of extraction industries (whose costs should increase over time, as the best resources get depleted), commodities that are produced but not extracted (e.g., agricultural commodities) and products that are manufactured. This points to the long-run cost trends ahead (pages 14-15).