Coal

-

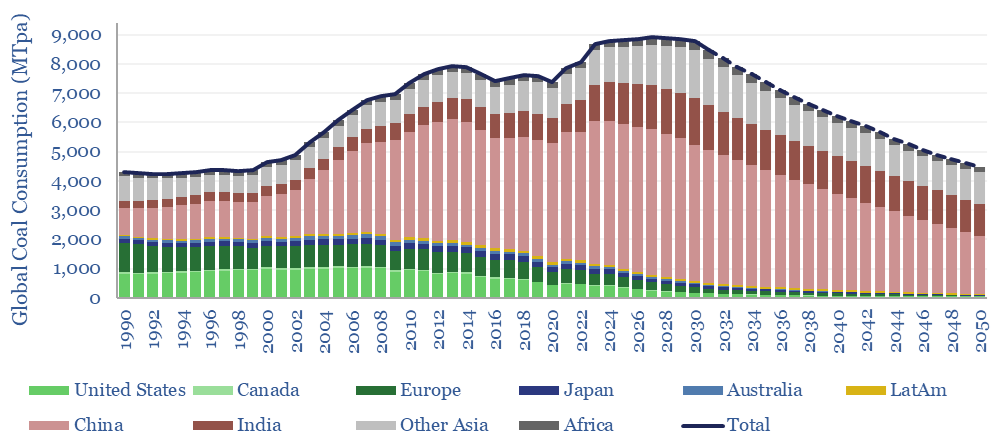

Global coal supply-demand: outlook in energy transition?

Global coal use likely hit a new all-time peak of 8.8GTpa in 2024, of which 7.6GTpa is thermal coal and 1.1GTpa is metallurgical. The largest consumers are China (5GTpa), India (1.3GTpa), other Asia (1.2GTpa), Europe (0.4GTpa) and the US (0.4GTpa). This model presents our forecasts for global coal supply-demand from 1990 to 2050.

-

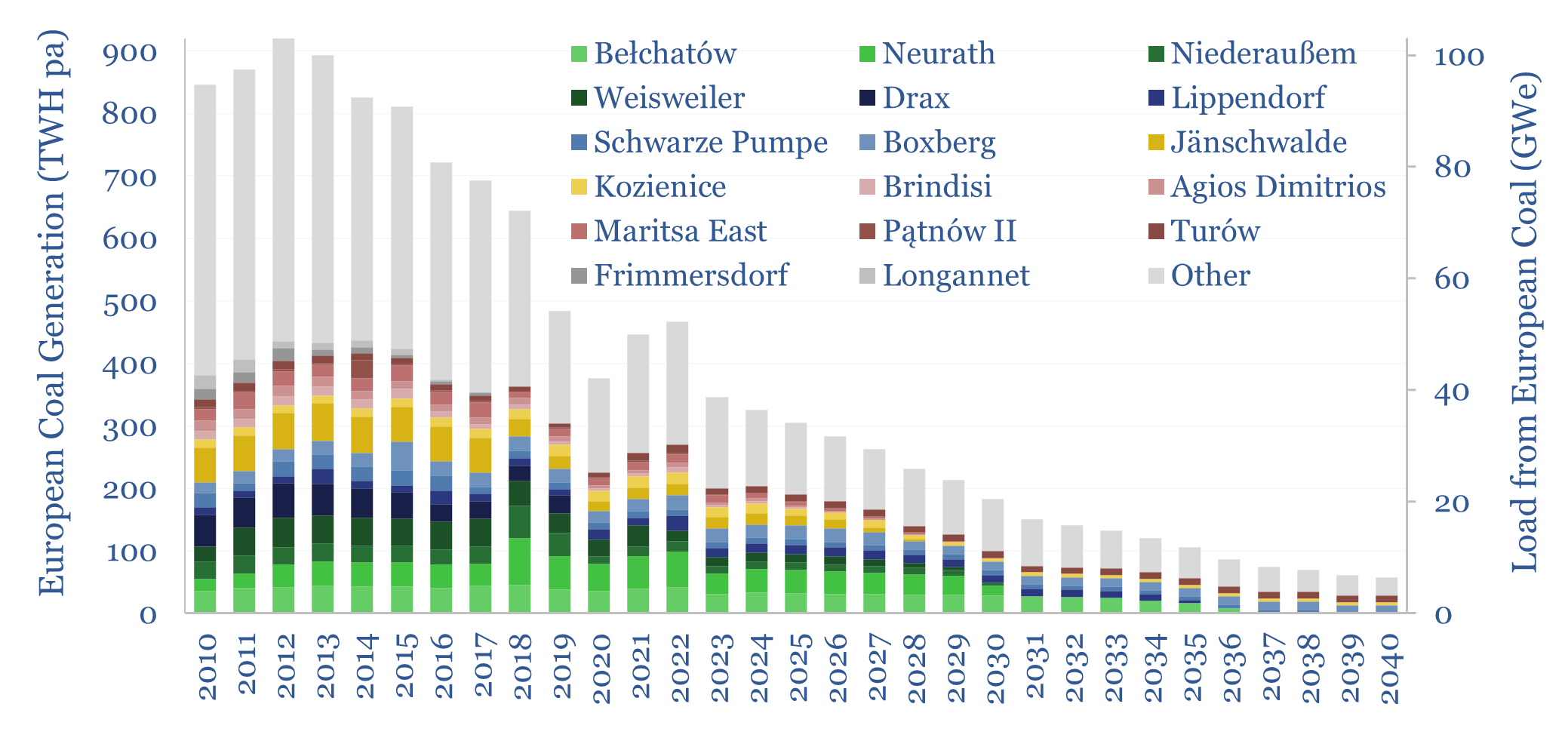

European coal generation by facility and coal plant closures?

Europe generated 350TWH of electricity from coal in 2023, having halved over the prior decade, and potentially declining to zero around 2040. We have recently been wondering whether this phase-back of coal is compatible with geopolitical priorities or the need to keep pace with the rise of AI. Hence this data-file tracks European coal generation…

-

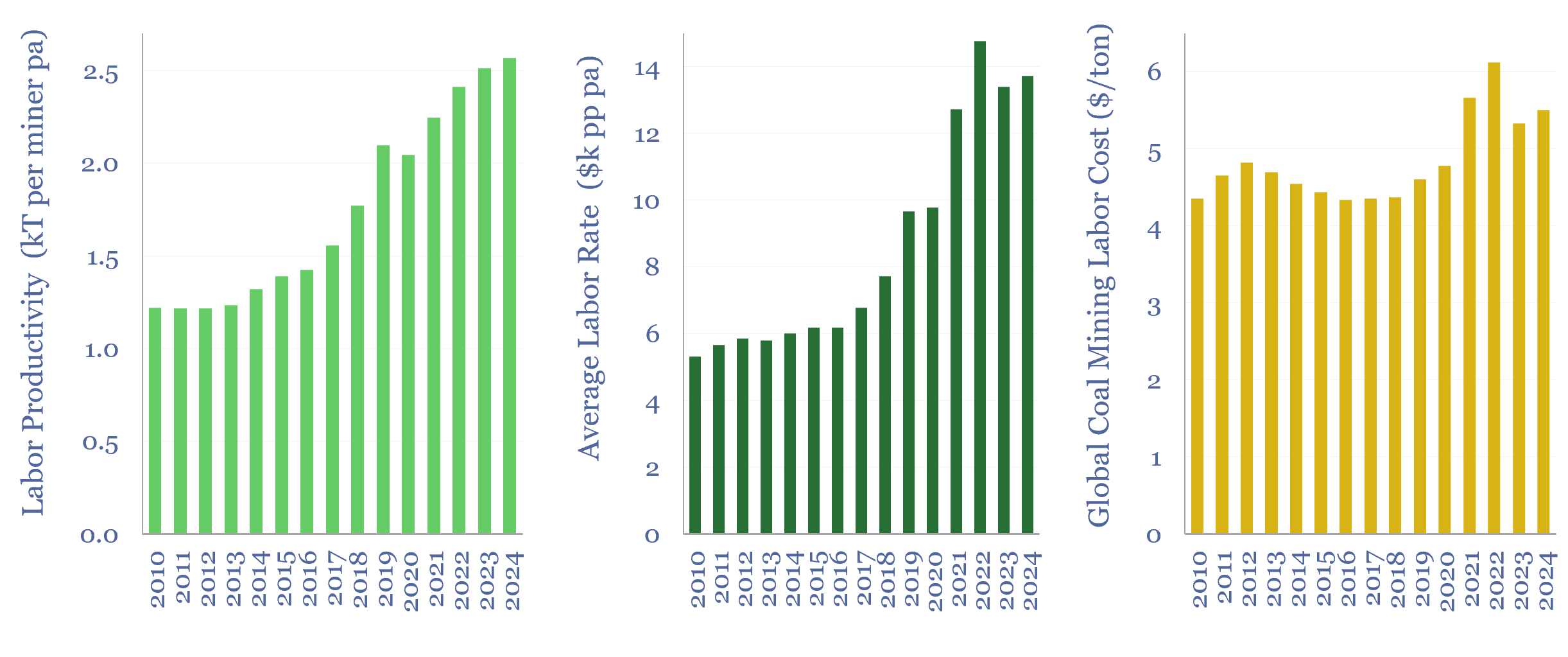

Labor costs of coal production: labor productivity and salaries?

This data-file estimates the labor costs of coal production, as a function of labor productivities and salaries, by region and over time. As a global average, across the 3M global coal mine employees captured in the data-file, labor productivity runs at 2,500 tons of coal per employee per year, average salary is $14k pp pa,…

-

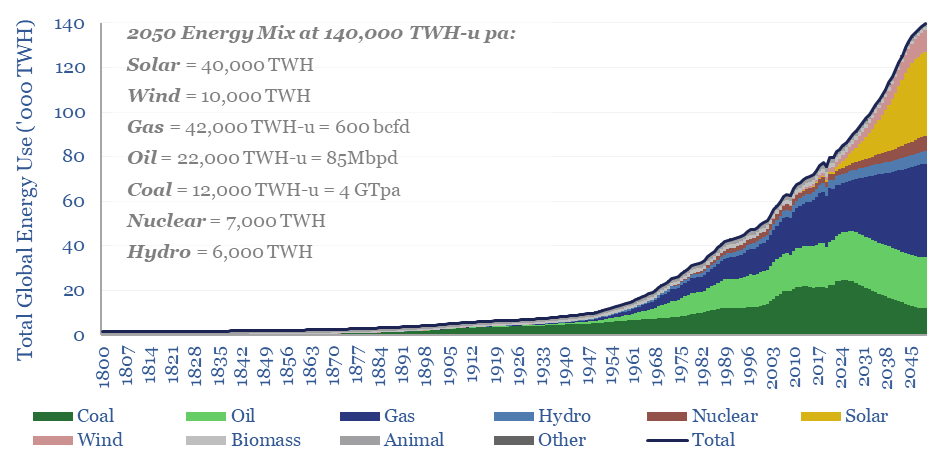

Energy transition: solar and gas -vs- coal hard reality?

This 15-page note outlines the largest changes to our long-term energy forecasts in five years. Over this time, we have consistently underestimated both coal and solar. Both are upgraded. But we also show how coal can peak after 2030. Global gas is seen rising from 400bcfd in 2023 to 600bcfd in 2050.

-

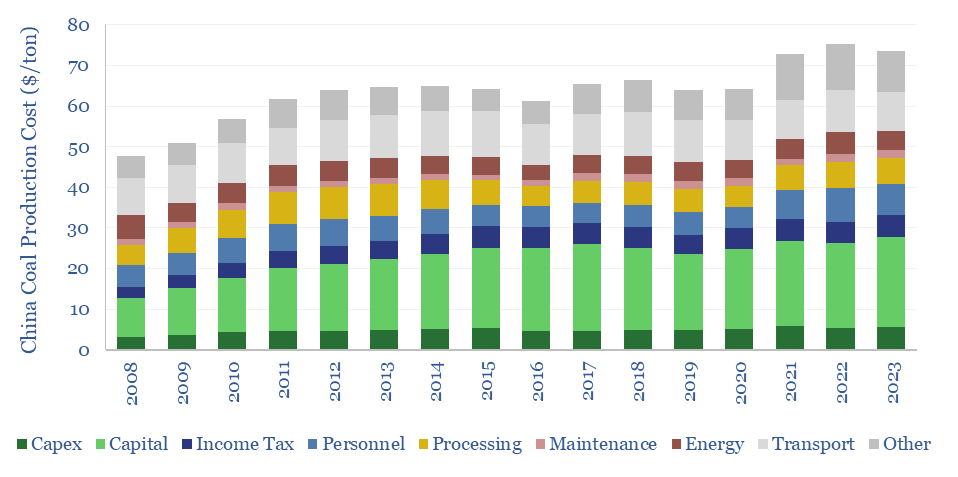

China coal production costs?

China coal production costs are estimated on a full-cycle basis in this data-file, averaging $75/ton across large listed miners, with assets in Shanxi, Inner Mongolia and Shaanxi. The costs are increasing at $1.3/ton/year, as mines move deeper and into smaller seams. Smaller regional have 1.5-2x higher costs again, and will hit LNG price parity around…

-

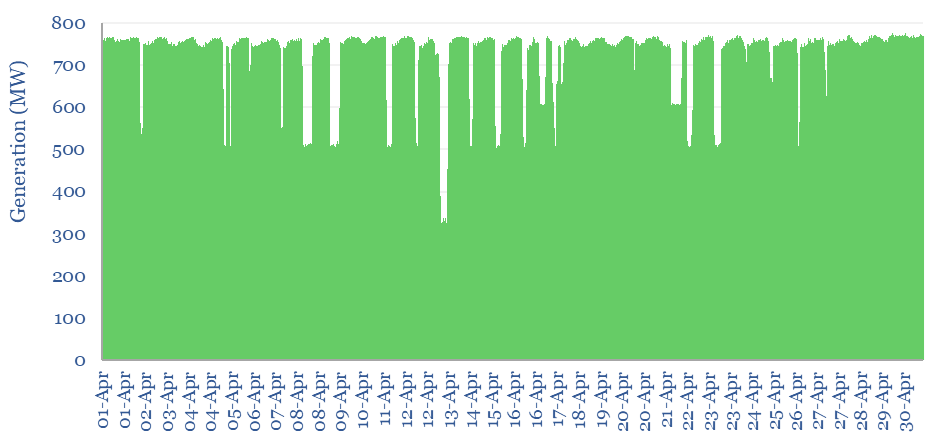

Coal power generation: minute-by-minute flexibility?

Coal power generation is aggregated in this data-file, at the largest single-unit coal power plant in Australia, across five-minute intervals, for the whole of 2023. The Kogan Creek coal plant produces stable baseload power, with average utilization rate of 85%. But it exhibits lower flexibility to backstop renewables than gas-fired generation.

-

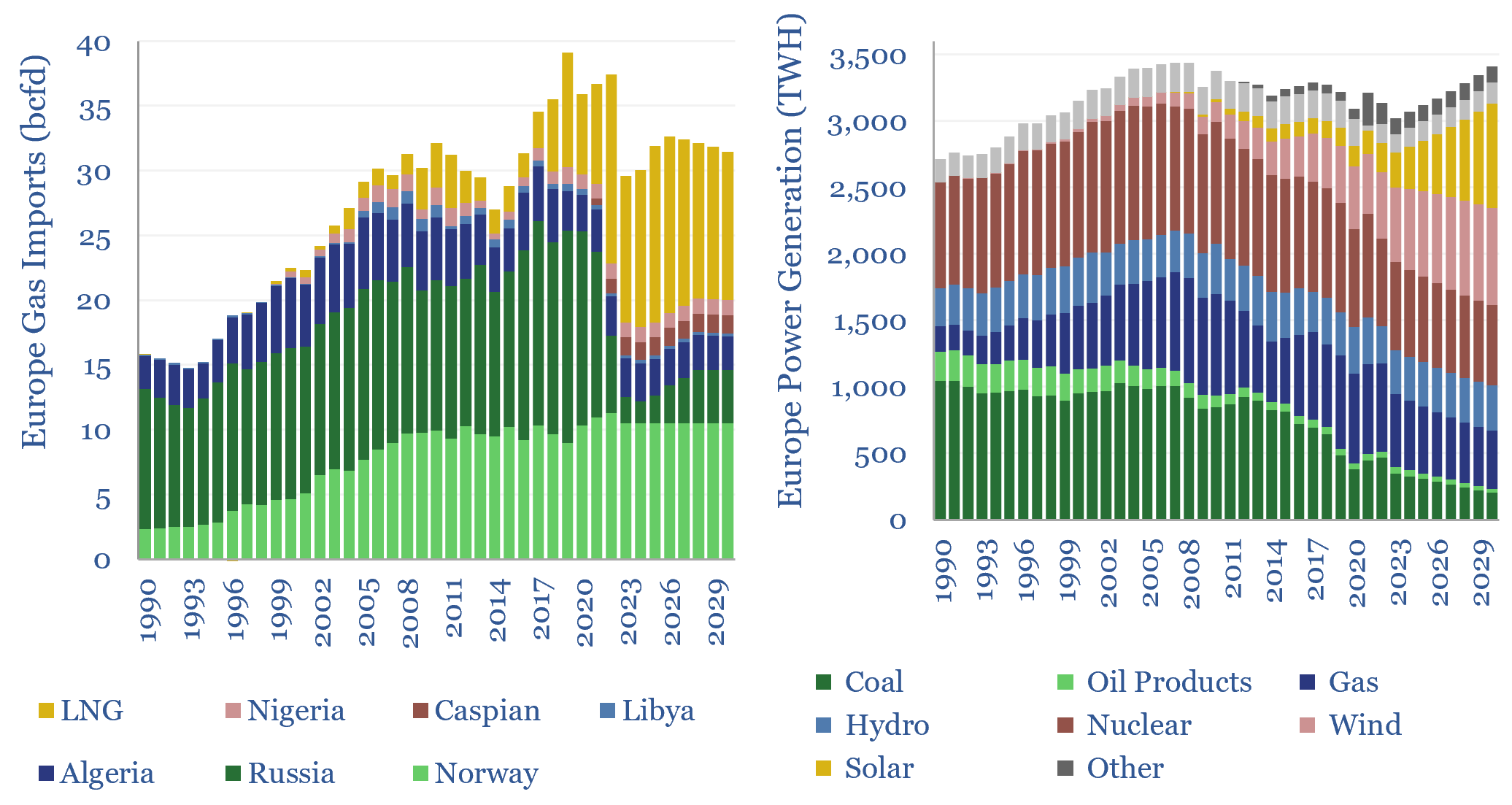

European gas and power model: natural gas supply-demand?

European gas and power markets will look better-supplied than they truly are in 2023-24. A dozen key input variables can be stress-tested in the data-file. Overall, we think Europe will need to source over 15bcfd of LNG through 2030, especially US LNG.

-

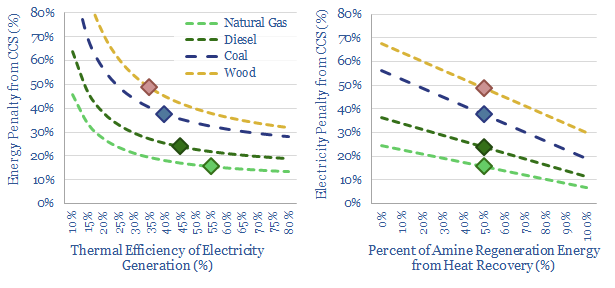

Post-combustion CCS: what energy penalties?

A thermal power plant converts 35-45% of the chemical energy in coal, biomass or pellets into electrical energy. So what happens to the other 55-65%? Accessing this waste heat can mean the difference between 20% and 60% energy penalties for post-combustion CCS. This 10-page note explores how much heat can be recaptured.

-

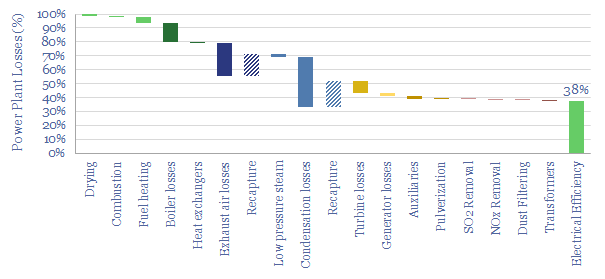

Thermal power plant: loss attribution?

This data-file is a simple loss attribution for a thermal power plant. For example, a typical coal-fired power plant might achieve a primary efficiency of 38%, converting thermal energy in coal into electrical energy. Our loss attribution covers the other 62% using simple physics and industry average data-points.

-

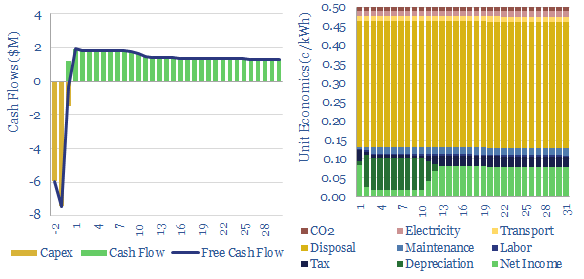

Electrostatic precipitator: costs of particulate removal?

Electrostatic precipitator costs can add 0.5 c/kWh onto coal or biomass-fired electricity prices, in order to remove over 99% of the dusts and particulates from exhaust gases. Electrostatic precipitators cost $50/kWe of up-front capex to install. Energy penalties average 0.2%. These systems are also important upstream of CCS plants.

Content by Category

- Batteries (88)

- Biofuels (44)

- Carbon Intensity (49)

- CCS (63)

- CO2 Removals (9)

- Coal (38)

- Company Diligence (93)

- Data Models (834)

- Decarbonization (160)

- Demand (110)

- Digital (59)

- Downstream (44)

- Economic Model (203)

- Energy Efficiency (75)

- Hydrogen (63)

- Industry Data (278)

- LNG (48)

- Materials (82)

- Metals (79)

- Midstream (43)

- Natural Gas (148)

- Nature (76)

- Nuclear (23)

- Oil (164)

- Patents (38)

- Plastics (44)

- Power Grids (127)

- Renewables (149)

- Screen (116)

- Semiconductors (30)

- Shale (51)

- Solar (67)

- Supply-Demand (45)

- Vehicles (90)

- Wind (43)

- Written Research (352)