This data-file is an Excel visualizer for some of the key headline metrics around renewables’ share of global energy: such as total global energy use, electricity generation by source, wind penetration and solar penetration; broken down country-by-country, and showing how these metrics have changed over time, in an easy-to-compare visual format.

Global useful energy consumption stood at c82,000 TWH in 2023, rising at 2.5% per year in the past decade. It will most likely continue rising to over 120,000 TWH pa by 2050 (historical data here and region by region forecasts here).

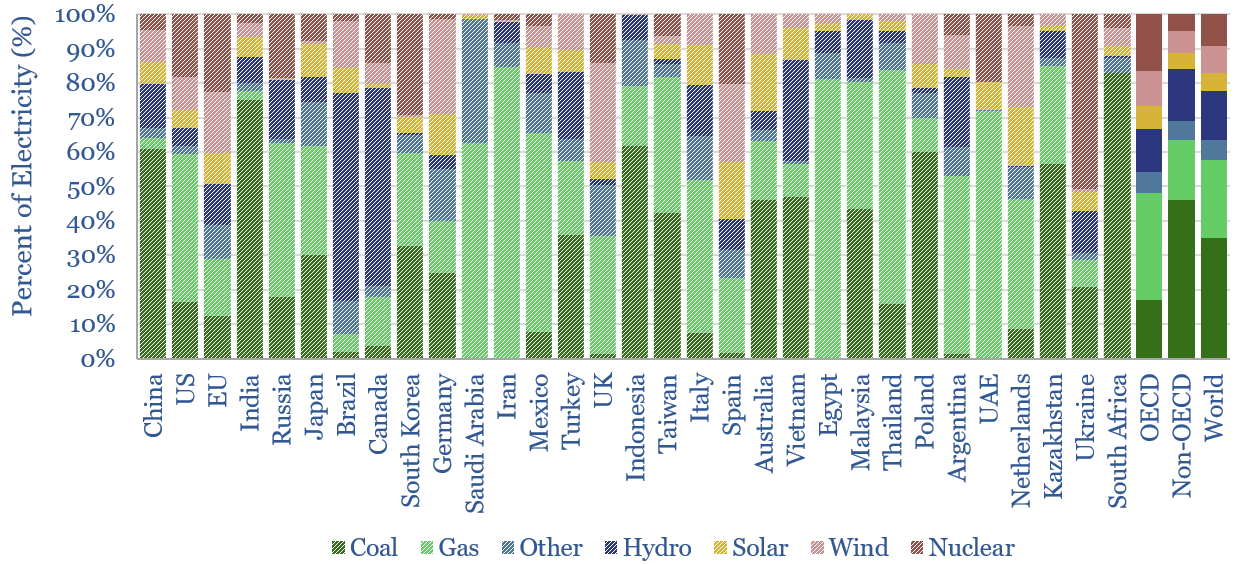

Electricity comprises 36% of total useful energy, with c30,000 TWH generated in 2023, and the remainder is for heat, motion, materials.

Electricity’s 36% share (as a percent of total useful energy) has changed remarkably little over the past decade, in our assessment, although electricity did increase from 16% to 18% of total primary energy.

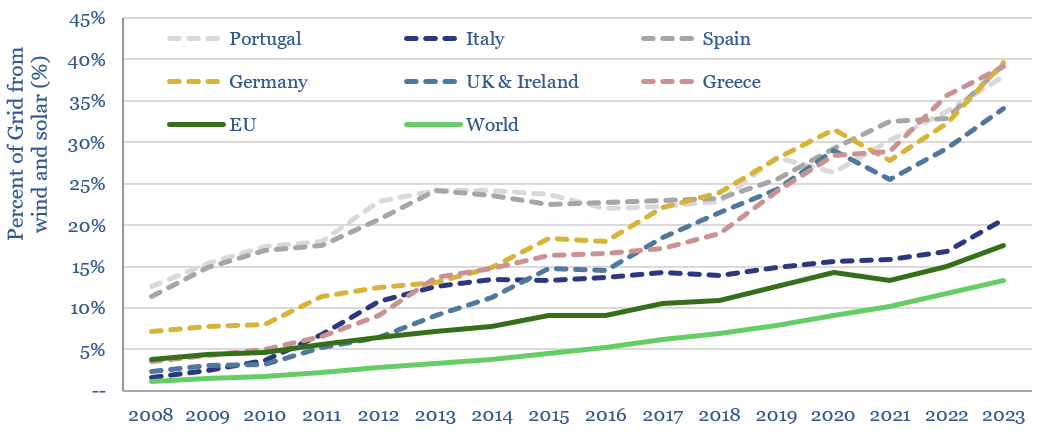

Wind and solar now make up 13% of all global electricity, of which 60% is wind, 40% is solar; making up 17% of OECD electricity and 11% of non-OECD.

Wind and solar’s 12% share of global electricity is up from 3% a decade ago. This 9% increase has displaced coal (40% to 35%), but more disappointingly for CO2 intensity, also nuclear (11% to 9%) and hydro (16% to 15%), while natural gas remains at 23%.

France makes an interesting but also slightly depressing case study from a Scope 4 CO2 perspective. From 2012->2022, wind and solar increased from 3% to 12% of the total grid (+9%), but over the same timeframe, nuclear declined from 75% to 63% (-12%) so the share of clean energy in the grid mix actually fell by 4pp overall.

The “renewables frontier” is that ten European countries generated over 30% of their electricity from wind and solar in 2023 (chart below). California is similar, although the US overall generated 15% of its electricity from wind and solar in 2023 (TSE model here).

Denmark is the absolute wind+solar leader and has generated 50-70% of its electricity from wind+solar since 2017, with wind and solar generation equivalent to 68% of its grid in 2023. But this high penetration is achieved by exporting excess power, e.g., to Germany.

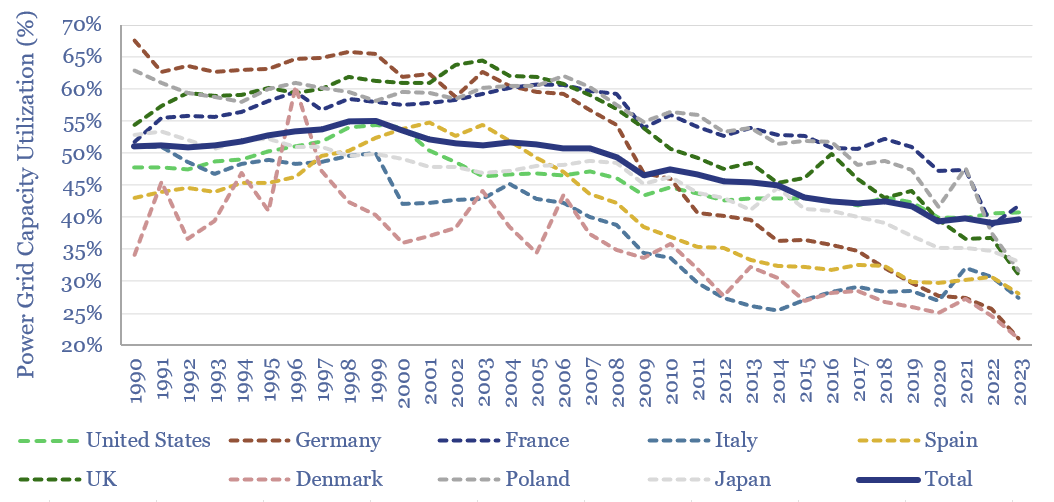

Paradoxically, wind and solar penetration does seem to correlate with higher electricity costs (data here), which in our view is linked to rising power grid system costs, which are often overlooked in over-simplified LCOE analysis. As a concrete example, Denmark, lauded as a wind+solar leader above, has the highest retail electricity price of any country in our sample.

How does grid utilization change as renewables ramp up? We think that the main reason increasingly renewables-heavy grids have seen higher costs is that the ramp of renewables reduces the average utilization factor of infrastructure across the grid. In the average grid in our chart below, the aggregated utilization factor has fallen from 55% at peak in 1998 to 40% in 2023. The declines are sharpest in countries that have ramped renewables fastest. This spreads the fixed costs of generation, transmission and distribution infrastructure across fewer units of output per MW of capacity, which in turn is inflationary.

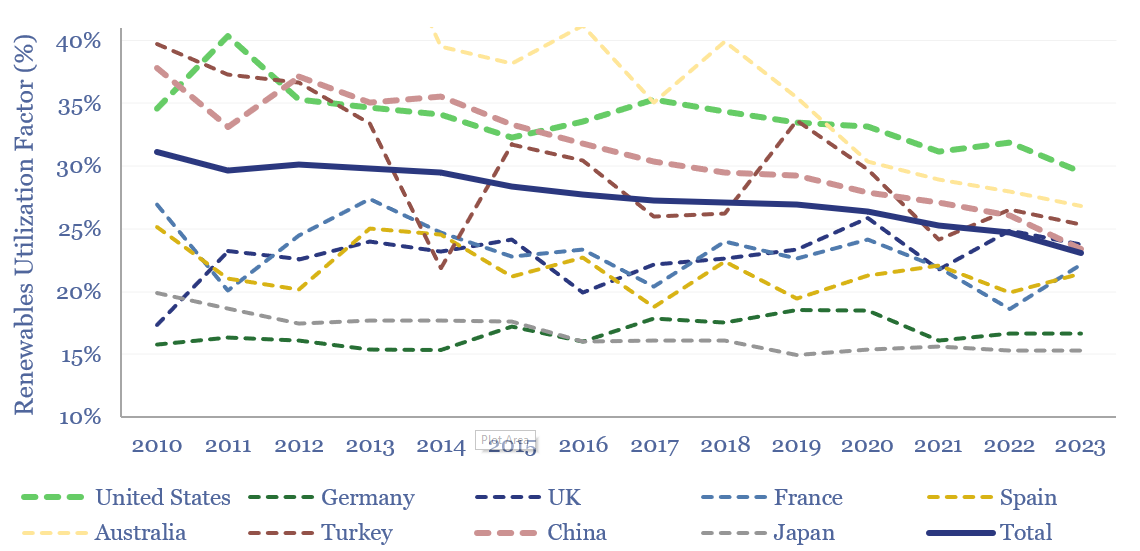

Utilization factors (aka availability factors) are also plotted for wind, solar and hydro, in a dozen core countries, going back to 2010. A key finding is that the annual utilization of renewables is volatile, especially when considering smaller areas, or more limited subsets of renewable assets. Hence we see growing volatility in energy markets are renewables gain share, creating opportunities for traders and midstream companies. The data-file contains a ‘calculator’ to estimate the growing volatility of supply balances as renewables gain share.

Slow-downs. The ramp to 20-25% occurred more quickly in some of these countries, while the subsequent ramp sometimes (not always) occurred more slowly, and this may be the time that storage and demand-shifting started becoming more important.

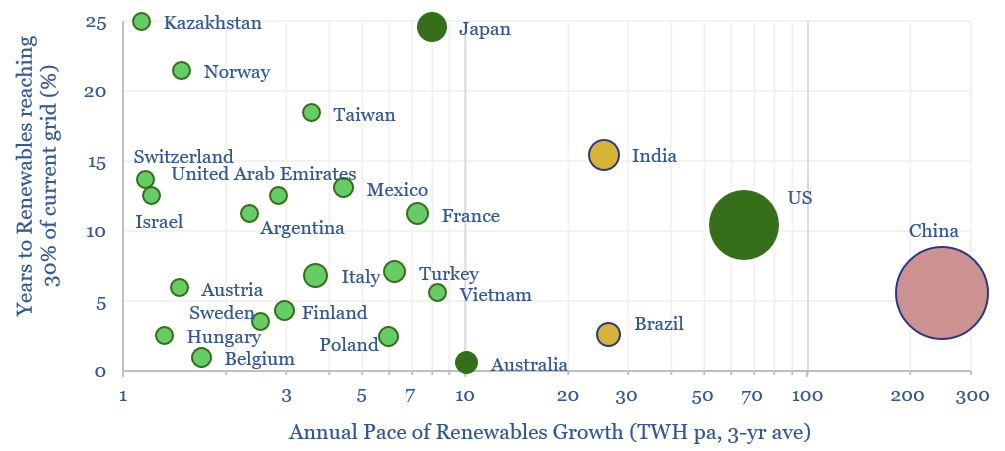

Intermittency markets? Most countries in our screen are on course to reach 30% wind and solar penetrations within 15 years, at the current run-rate, again suggesting the dawn of demand-shifting, storage and intermittency solutions in this timeframe (chart below).

The cleanest grids in the world, however, belong to Norway (88% hydro, 9% wind) and Sweden (40% hydro, 29% nuclear, 21% wind, 1.9% solar), where nuclear and hydro can also buffer renewables (note here).

China, India and Indonesia together comprise c40% of global electricity, comparable to the entire OECD’s electricity generation, and retain over 60% coal in their power mixes.

Despite rising renewables, coal-fired electricity, gas-fired electricity, total oil, coal and gas use all made new highs in 2021-23. Our overview of China’s coal trajectory is here.

Staggering coal numbers. Global electricity generated from coal rose to 10,500 TWH in 2023, an all time peak, 2.5x higher than all global wind and solar generation. Fifteen years ago, OECD and non-OECD countries were both generating 4,000 TWH pa from coal. The OECD has declined to 2,000 TWH, while the non-OECD has increased to over 8,000 TWH. Increasingly we think that decarbonization requires an all of the above approach, which includes ramping renewables as fast as possible AND cultivating low carbon gas, CCS, nature.

A main source for this visualizer into renewables’ share of global energy is the exceptionally useful and thorough data provided in Energy Institute (linked here) and before that, BP’s Statistical Review of World Energy (linked here). The analysis, data-scrubbing and visualizations are our own. The data-file was last updated in 2024, with FY23 data.