Using a commodity more efficiently can cause its demand to rise not fall, as greater efficiency opens up unforeseen possibilities. This is Jevons’ Paradox. Our 16-page report finds it is more prevalent than we expected. Efficiency gains underpin 25% of our roadmap to net zero. To be effective, commodity prices must rise, otherwise rebound effects raise demand.

Jevons’ Paradox was articulated by William Stanley Jevons, in 1865, after observing a +8x improvement in steam engine efficiency from 1710 to 1860, causing British coal use not to fall, but to rise +18x to 80MTpa, and +6x in per capita terms.

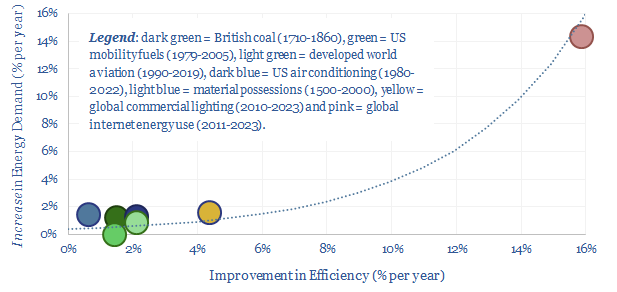

The Jevons Effect is a particular type of rebound effect. All rebound effects involve new demand counteracting the impacts of efficiency improvements (i.e., 3% efficiency gain – 1% rebound effect = 2% net energy reduction). But in the Jevons Effect, specifically, the new demand is of a larger magnitude than the efficiency gain itself (i.e., 3% efficiency gain – 5% rebound effect = 2% overall increase in energy demand).

The Jevons Effect matters as our roadmap to net zero wants to see 25% of all decarbonization coming from efficiency gains, while other forecasters have even proposed that a large step-up in efficiency gains will see net global energy demand decline by as much as 20% by 2050 (although this assumption looks dangerously wrong to us, note here).

This report aims to quantify the Jevons Effect, objectively, using as much data as possible from our library of 1,000 data-files and models, built up over the past five-years. Overall, we found the Jevons Effect to be much more prevalent than we expected.

Where the Jevons Effect occurs, across seven large areas reviewed in the report, each 1% improvement in energy efficiency has coincided with a 0.7% net increase in energy demand. In other areas, we also find rebound effects, where each 1% improvement in energy efficiency is muted by a c0.5% rebound. These may be useful rules of thumb.

Examples considered in the report include the rise of the internet (pages 5-6), commercial lighting (pages 7-8), material possessions (page 9), US automotive fuel economy standards (pages 10-11), developed world aviation (page 12), US air conditioning (page 13-14) and US residential electricity use (page 15).

Our conclusions from the analysis suggest it will be harder to use energy efficiency initiatives as a route to decarbonization, unless underlying commodity prices also trend higher over time.

Otherwise energy demand will surprise to the upside. Vast new markets will also be unlocked by efficiency initiatives. Some of these new and evolving markets are also linked to human progress and it would be quite sad if they were stifled by decarbonization aspirations.