-

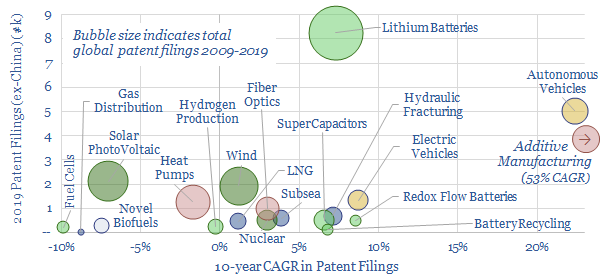

Energy transition technologies: the pace of progress?

This 3-page note captures over 250,000 patents (ex-China) to assess the pace of progress in different energy transition technologies, yielding insights into batteries (high activity), autonomous vehicles and additive manufacturing (fastest acceleration), wind and solar (maturing), fuel cells and biofuels (waning) and other technologies.

-

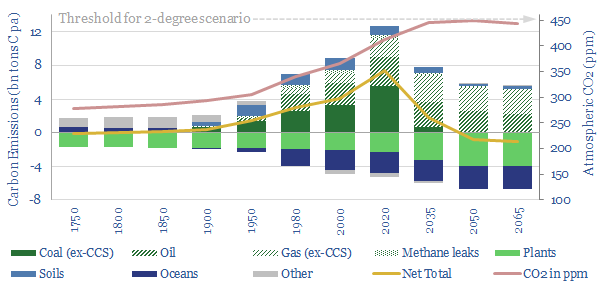

Nature based solutions to climate change: a summary

Nature based solutions to climate change are among the largest and lowest cost opportunities to decarbonize the global energy system. Looking across 1,000 pages of research and over 200 data files, this short note summarizes our findings.

-

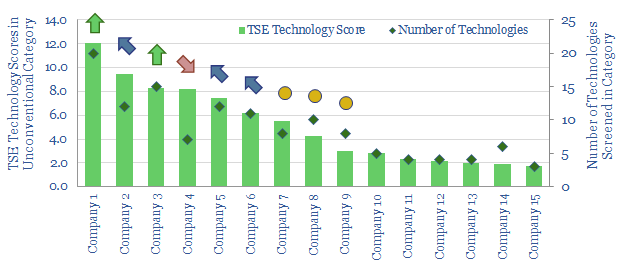

US shale: the quick and the dead?

It is no longer possible to compete in the US shale industry without leading digital technologies. This 10-page note outlines best practices, based on 500 patents and 650 technical papers. Chevron, Conoco and ExxonMobil lead our screens. Disconcertingly absent from the leader-board is EOG, whose edge may have been eclipsed.

-

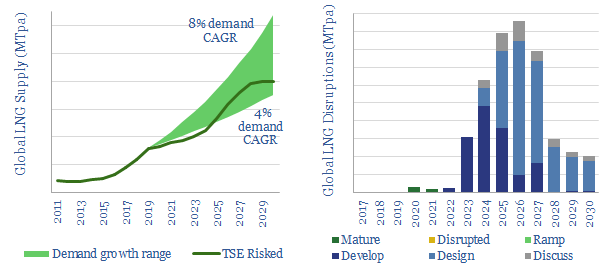

LNG: deep disruptions?

There is now a potential 100MTpa shortfall in 2024-26 LNG markets. The current COVID-crisis will likely cause a further 15-45MTpa of supply-disruptions (delays in 2022-24, deferrals in 2024-7). This 6-page note draws out our top insights from looking line-by-line through 120 LNG projects.

-

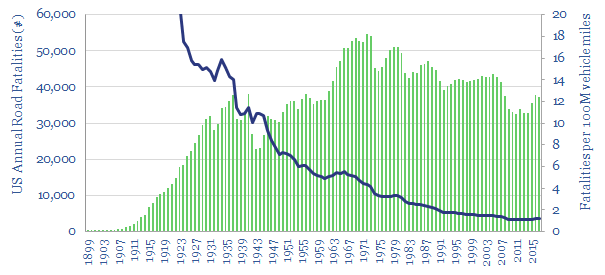

More dangerous than coronavirus? The safety case for digital and remote operations.

Remote working, digital de-manning, drones and robotics — all of these themes will structurally accelerate in the aftermath of the COVID crisis. This short note considers the safety consequences. They are as significant as COVID itself.

-

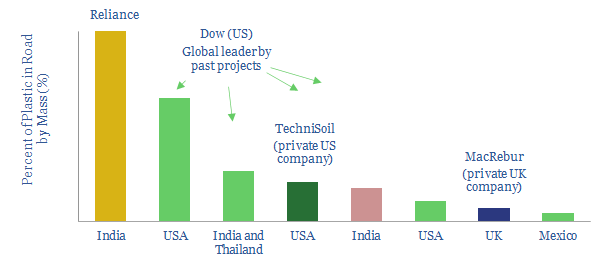

Turn the Plastic into Roads?

The opportunity is emerging to absorb mixed plastic waste, displacing bitumen from road asphalts. We find strong economics, with net margins of $200/ton of plastic, deflating the materials costs of roads by c4%. The challenge is scaling the opportunity. Leading companies and projects are profiled in our 6-page note.

-

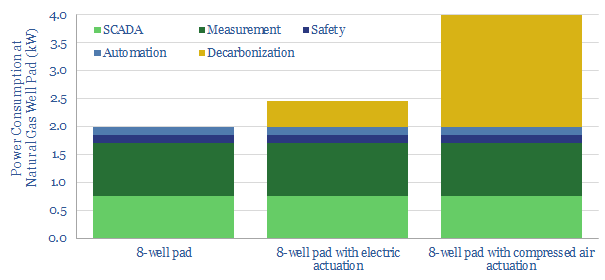

Qnergy: reliable remote power to mitigate methane?

This short note profiles Qnergy, the leading manufacturer of Stirling-design engines, which generate 1-10 kW of power, in remote areas, where a grid connection is not available. The units are particularly economical for mitigating methane emissions, with a potential abatement cost of $20/ton.

-

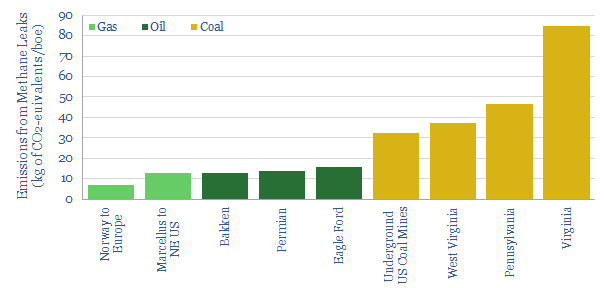

Do Methane Leaks Detract from Natural Gas?

Some commentators criticize that methane leaks detract from natural gas as a low-carbon fuel in the energy transition. Leaking 2.7-3.5% of natural gas could make gas “dirtier than coal”. However, when considered apples-to-apples, we find natural gas value chains leak 30% less methane than oil and 70% less methane than underground coal mining. This note…

-

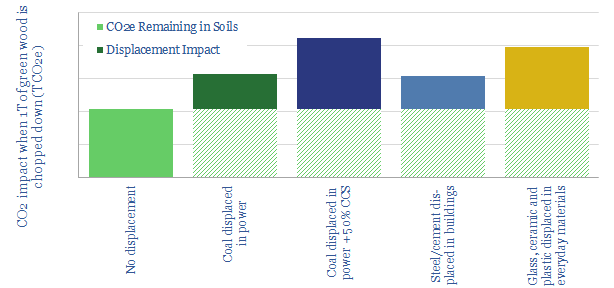

If a tree falls in a forest…

Forestry projects can sequester 15bn tons of CO2 per annum, helping to accommodate 400TCF of gas per year and 85Mbpd per oil in a fully decarbonized energy system by 2050. Economics are competitive. But what happens when the forests are cut down? This short note addresses the pushback.

-

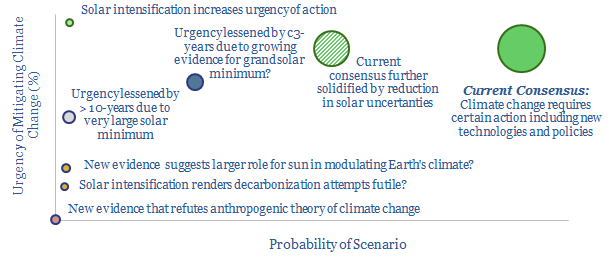

Climate science: staring into the sun?

Our research focuses on technologies that can deliver an energy transition. But it is always important to stress-test your premises, and consider what new evidence could unseat them. Hence this note looks at the sun, the largest uncertainty in climate modelling, and how new data from new satellites could shift scientific and market sentiment.

Content by Category

- Batteries (89)

- Biofuels (44)

- Carbon Intensity (49)

- CCS (63)

- CO2 Removals (9)

- Coal (38)

- Company Diligence (95)

- Data Models (840)

- Decarbonization (160)

- Demand (110)

- Digital (60)

- Downstream (44)

- Economic Model (205)

- Energy Efficiency (75)

- Hydrogen (63)

- Industry Data (279)

- LNG (48)

- Materials (82)

- Metals (80)

- Midstream (43)

- Natural Gas (149)

- Nature (76)

- Nuclear (23)

- Oil (164)

- Patents (38)

- Plastics (44)

- Power Grids (130)

- Renewables (149)

- Screen (117)

- Semiconductors (32)

- Shale (51)

- Solar (68)

- Supply-Demand (45)

- Vehicles (90)

- Wind (44)

- Written Research (355)