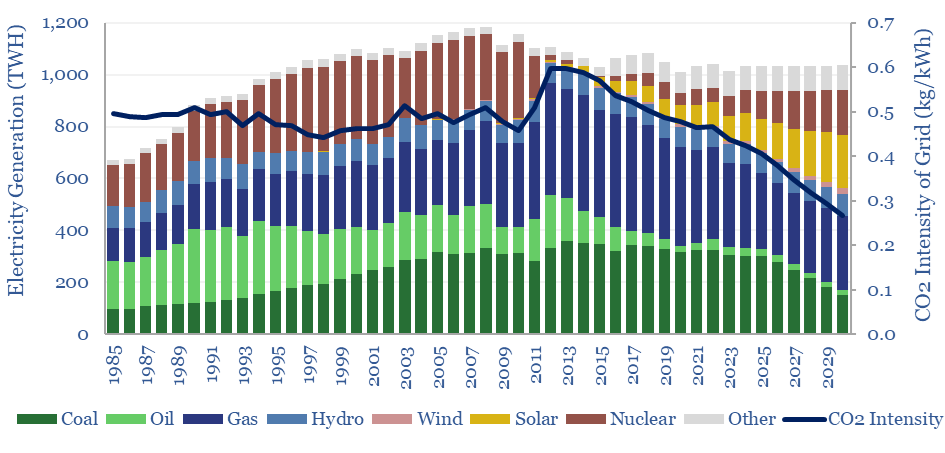

Japan’s gas and power markets are broken down by end use, traced back to 1990, and forecast forwards to 2030 in this model. Japan’s electricity demand now grows at 0.3% pa. Ramping renewables, nuclear and gas back-ups could halve Japan’s total grid CO2 intensity to below 0.25 kg/kWh by 2030.

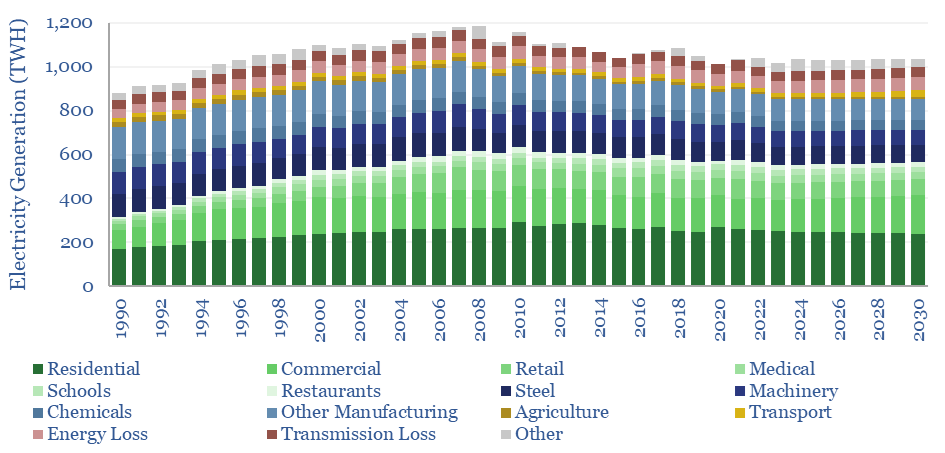

After declining at -0.7% per year in the past decade, electricity demand will begin growing again, at +0.3% pa through 2030, due to the rise of electric vehicles and increasing electricity demand for data-centers linked to the rise of AI.

Japan’s electricity demand is 8.1 MWH pp pa, compared with 6 MWH pp pa in Europe and 13 MWH pp pa in the US. 25% is residential, 30% is commercial, 30% is industrial.

A detailed breakdown of Japan’s electricity demand reminds us of the ubiquity of energy. 8% is used for making steel, 7% for manufacturing machinery, 5% for chemicals. Another 3% is used in supermarkets, 3% in medical facilities, 2.5% in schools, 2% in restaurants, and 1.6% for Japan’s amazing electric railway system.

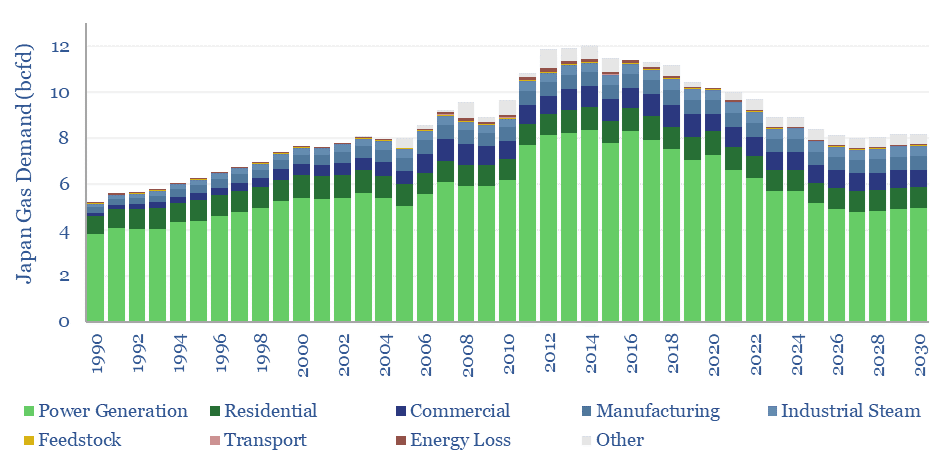

Japan’s gas market is unusual in that 65% of all the gas is used for electricity generation, much higher than in the US (38% of gas use) and Europe (25% of gas use).

The key reason is not that Japan generates a large portion of its electricity from gas (only c30% of the mix), but rather that non-electricity uses of gas are underdeveloped. For example, Japanese households still generate more heat from oil products than from gas, and 60% of Japan’s 3.4 Mbpd of oil use is outside of transportation.

Our outlook for Japan’s electricity mix is that wind and solar will double from 11% to 22% of the mix by 2030, and almost 100 TWH of nuclear restarts will increase nuclear from 8% to almost 20% of the mix.

A common finding across all of our research is that ramping renewables tends to displace coal more than gas (note below). Hence we think coal phase-downs could surprise, cutting coal use in power by c50% (1.5x more than official government targets).

The result is a mild pullback in Japan’s gas consumption, from 6bcfd in 2023 to 5bcfd in 2030, freeing up 7.5MTpa of LNG.

However, the best case scenario for Japanese decarbonization would hold gas use constant, especially if LNG supplies are available, displace more coal, and this could halve the CO2 intensity of Japanese power generation by 2030.

All of the numbers and input assumptions can be stress-tested in the model. Underlying data are from Japan’s Agency for Natural Resources and Energy. The data-file is also interesting to compare with our European, US, China and India energy models.